Welcome back to: Has quantum advantage been achieved?

In Part 1 of this mini-series on quantum advantage demonstrations, I told you about the idea of random circuit sampling (RCS) and the experimental implementations thereof. In this post, Part 2 out of 3, I will discuss the arguments and evidence for why I am convinced that the experiments demonstrate a quantum advantage.

Recall from Part 1 that to assess an experimental quantum advantage claim we need to check three criteria:

- Does the experiment correctly solve a computational task?

- Does it achieve a scalable advantage over classical computation?

- Does it achieve an in-practice advantage over the best classical attempt at solving the task?

What’s the issue?

When assessing these criteria for the RCS experiments there is an important problem: The early quantum computers we ran them on were very far from being reliable and the computation was significantly corrupted by noise. How should we interpret this noisy data? Or more concisely:

- Is random circuit sampling still classically hard even when we allow for whatever amount of noise the actual experiments had?

- Can we be convinced from the experimental data that this task has actually been solved?

I want to convince you today that we have developed a very good understanding of these questions that gives a solid underpinning to the advantage claim. Developing that understanding required a mix of methodologies from different areas of science, including theoretical computer science, algorithm design, and physics and has been an exciting journey over the past years.

The noisy sampling task

Let us start by answering the base question. What computational task did the experiments actually solve?

Recall that, in the ideal RCS scenario, we are given a random circuit on qubits and the task is to sample from the output distribution of the state obtained from applying the circuit to a simple reference state. The output probability distribution of this state is determined by the Born rule when I measure every qubit in a fixed choice of basis.

Now what does a noisy quantum computer do when I execute all the gates on it and apply them to its state? Well, it prepares a noisy version of the intended state and once I measure the qubits, I obtain samples from the output distribution of that noisy state.

We should not make the task dependent on the specifics of that state or the noise that determined it, but we can define a computational task based on this observation by fixing how accurate that noisy state preparation is. The natural way to do this is to use the fidelity

which is just the overlap between the ideal state and the noisy state. The fidelity is 1 if the noisy state is equal to the ideal state, and 0 if it is perfectly orthogonal to it.

Finite-fidelity random circuit sampling

Given a typical random circuit , sample from the output distribution of any quantum state whose fidelity with the ideal output state is at least .

Note that finite-fidelity RCS does not demand success for every circuit, but only for typical circuits from the random circuit ensemble. This matches what the experiments do: they draw random circuits and need the device to perform well on the overwhelming majority of those draws. Accordingly, when the experiments quote a single number as “fidelity”, it is really the typical (or, more precisely, circuit-averaged) fidelity that I will just call .

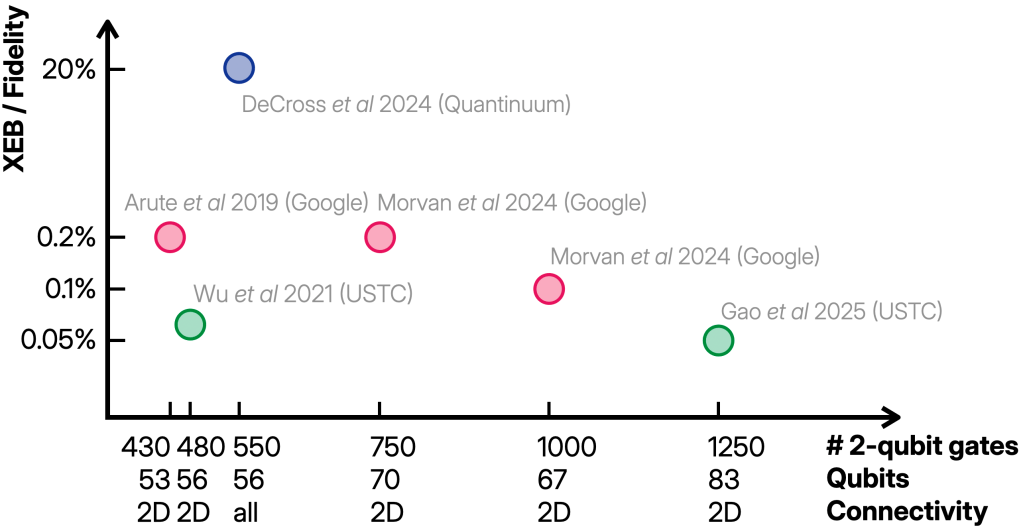

The noisy experiments claim to have solved finite-fidelity RCS for values of around 0.1%. What is more, they consistently achieve this value even as the circuit sizes are increased in the later experiments. Both the actual value and the scaling will be important later.

What is the complexity of finite-fidelity RCS?

Quantum advantage of finite-fidelity RCS

Let’s start off by supposing that the quantum computation is (nearly) perfectly executed, so the required fidelity is quite large, say, 90%. In this scenario, we have very good evidence based on computational complexity theory that there is a scalable and in-practice quantum advantage for RCS. This evidence is very strong, comparable to the evidence we have for the hardness of factoring and simulating quantum systems. The intuition behind it is that quantum output probabilities are extremely hard to compute because of a mechanism behind quantum advantages: destructive interference. If you are interested in the subtleties and the open questions, take a look at our survey.

The question is now, how far down in fidelity this classical hardness persists? Intuitively, the smaller we make , the easier finite-fidelity RCS should become for a classical algorithm (and a quantum computer, too), since the freedom we have in deviating from the ideal state in our simulation becomes larger and larger. This increases the possibility of finding a state that turns out to be easy to simulate within the fidelity constraint.

Somewhat surprisingly, though, finite-fidelity RCS seems to remain hard even for very small values of . I am not aware of any efficient classical algorithm that achieves the finite-fidelity task for significantly away from the baseline trivial value of . This is the value a maximally mixed or randomly picked state achieves because a random state has no correlation with the ideal state (or any other state), and is exactly what you expect in that case (while 0 would correspond to perfect anti-correlation).

One can save some classical runtime compared to solving near-ideal RCS by exploiting a reduced fidelity, but the costs remain exponential. To classically solve finite-fidelity RCS, the best known approaches are reported in the papers that performed classical simulations of finite-fidelity RCS with the parameters of the first Google and USTC experiment (classSim1, classSim2). To achieve this, however, they needed to approximately simulate the ideal circuits at an immense cost. To the best of my knowledge, all but those first two experiments are far out of reach for these algorithms.

Getting the scaling right: weak noise and low depth

So what is the right value of at which we can hope for a scalable and in-practice advantage of RCS experiments?

When thinking about this question, it is helpful to keep a model of the circuit in mind that a noisy experiment runs. So, let us consider a noisy circuit on qubits with layers of gates and single-qubit noise of strength on every qubit in every layer. In this scenario, the typical fidelity with the ideal state will decay as .

Any reasonably testable value of the fidelity needs to scale as , since eventually we need to estimate the average fidelity from the experimental samples and this typically requires at least samples, so exponentially small fidelities are experimentally invisible. The polynomial fidelity is also much closer to the near-ideal scenario (90%) than the trivial scenario (). While we cannot formally pin this down, the intuition behind the complexity-theoretic evidence for the hardness of near-ideal RCS persists into the regime: to sample up to such high precision, we still need a reasonably accurate estimate of the ideal probabilities, and getting this is computationally extremely difficult. Scalable quantum advantage in this regime is therefore a pretty safe bet.

How do the parameters of the experiment and the RCS instances need to scale with the number of qubits to experimentally achieve the fidelity regime? The limit to consider is one in which the noise rate decreases with the number of qubits, while the circuit depth is only allowed to increase very slowly. It depends on the circuit architecture, i.e., the choice of circuit connectivity, and the gate set, through a constant as I will explain in more detail below.

Weak-noise and low-depth scaling

(Weak noise) The local noise rate of the quantum device scales as .

(Low depth) The circuit depth scales as .

This limit is such that we have a scaling of the fidelity as for some constant . It is also a natural scaling limit for noisy devices whose error rates gradually improve through better engineering. You might be worried about the fact that the depth needs to be quite low but it turns out that there is a solid quantum advantage even for -depth circuits.

The precise definition of the weak-noise regime is motivated by the following observation. It turns out to be crucial for assessing the noisy data from the experiment.

Fidelity versus XEB: a phase transition

Remember from Part 1 that the experiments measured a quantity called the cross-entropy benchmark (XEB)

The XEB averages the ideal probabilities corresponding to the sampled outcomes from experiments on random circuits . Thus, it correlates the experimental and ideal output distributions of those random circuits. You can think of it as a “classical version” of the fidelity: If the experimental distribution is correct, the XEB will essentially be 1. If it is uniformly random, the XEB is 0.

The experiments claimed that the XEB is a good proxy for the circuit-averaged fidelity given by , and so we need to understand when this is true. Fortunately, in the past few years, alongside with the improved experiments, we have developed a very good understanding of this question (WN, Spoof2, PT1, PT2).

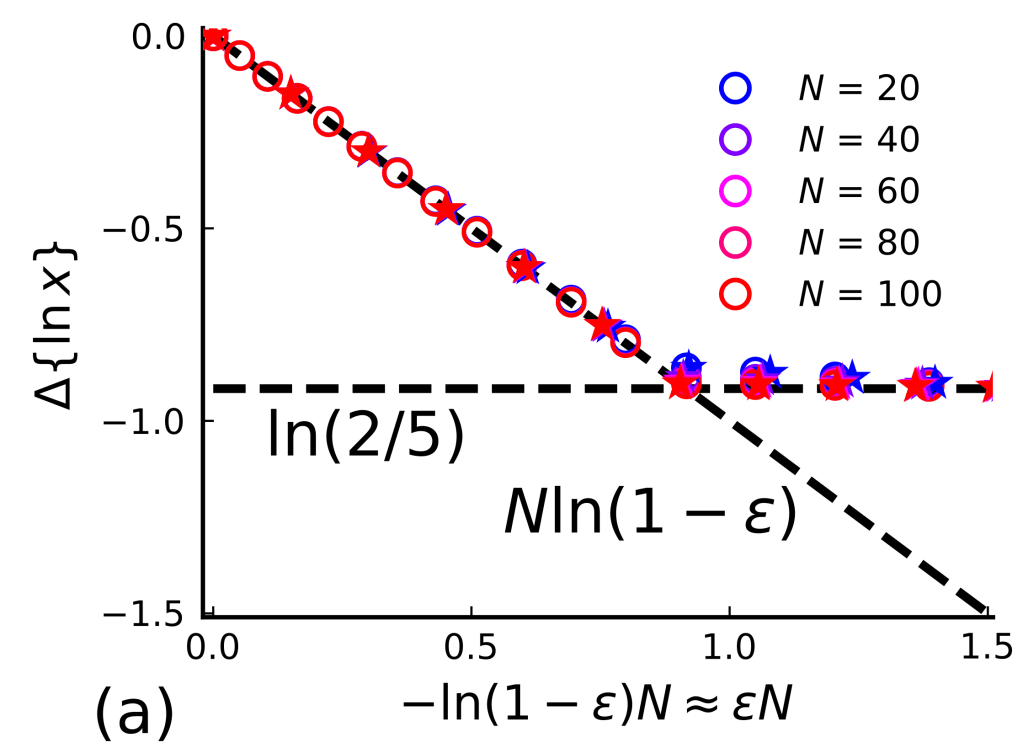

It turns out that the quality of correspondence between XEB and average fidelity depends strongly on the noise in the experimental quantum state. In fact, there is a sharp phase transition: there is an architecture-dependent constant such that when the experimental local noise rate , then the XEB is a good and reliable proxy for the average fidelity for any system size and circuit depth . This is exactly the weak-noise regime. Above that threshold, in the strong noise regime, the XEB is an increasingly bad proxy for the fidelity (PT1, PT2).

Let me be more precise: In the weak-noise regime, when we consider the decay of the XEB as a function of circuit depth , the rate of decay is given by , i.e., the XEB decays as . Meanwhile, in the strong-noise regime the rate of decay is constant, giving an XEB decay as for a constant . At the same time, the fidelity decays as regardless of the noise regime. Hence, in the weak-noise regime, the XEB is a good proxy of the fidelity, while in the strong noise regime, there is an exponentially increasing gap between the XEB (which remains large) and the fidelity (which continues to decay exponentially). regardless of the noise regime.

This is what the following plot shows. We computed it from an exact mapping of the behavior of the XEB to the dynamics of a statistical-mechanics model that can be evaluated efficiently. Using this mapping, we can also compute the noise threshold for whichever random circuit family and architecture you are interested in.

Where are the experiments?

We are now ready to take a look at the crux when assessing the noisy data: Can we trust the reported XEB values as an estimator of the fidelity? If so, do the experiments solve finite-fidelity RCS in the solidly hard regime where ?

In their more recent paper (PT1), the Google team explicitly verified that the experiment is well below the phase transition, and it turns out that the first experiment was just at the boundary. The USTC experiments had comparable noise rates, and the Quantinuum experiment much better ones. Since fidelity decays as , but the reported XEB values stayed consistently around 0.1% as was increased, the experimental error rate of the experiments improved even better than the scaling required for the weak-noise regime, namely, more like . Altogether, the experiments are therefore in the weak-noise regime both in terms of absolute numbers relative to and the required scaling.

Of course, to derive the transition, we made some assumptions about the noise such as that the noise is local, and that it does not depend much on the circuit itself. In the advantage experiments, these assumptions about the noise are characterized and tested. This is done through a variety of means at increasing levels of complexity, including detailed characterization of the noise in individual gates, gates run in parallel, and eventually in a larger circuit. The importance of understanding the noise shows in the fact that a significant portion of the supplementary materials of the advantage experiments is dedicated to getting this right. All of this contributes to the experimental justification for using the XEB as a proxy for the fidelity!

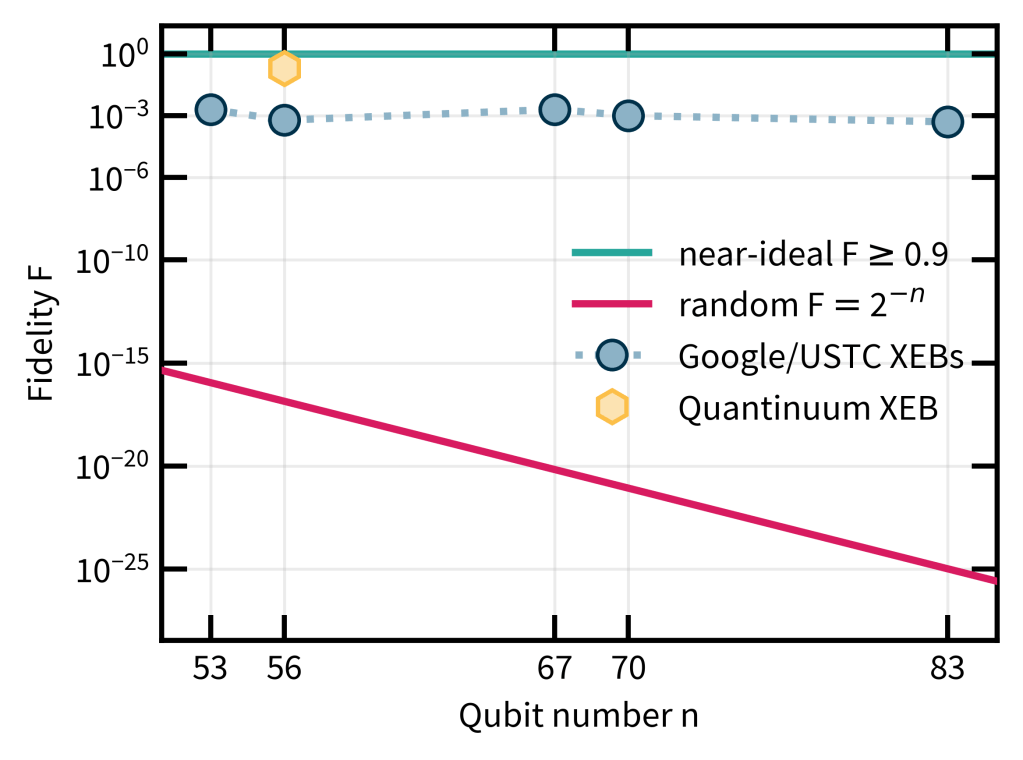

The data shows that the experiments solved finite-fidelity RCS for values of above the constant value of roughly 0.1% as the experiments grew. In the following plot, I compare the experimental fidelity values to the near-ideal scenario on the one hand, and the trivial value on the other hand. Viewed at this scale, the values of for which the experiment solved finite-fidelity RCS are indeed vastly closer to the near-ideal value than the trivial baseline, which should boost our confidence that reproducing samples at a similar fidelity is extremely challenging.

The phase transition matters!

You might be tempted to say: “Well, but is all this really so important? Can’t I just use XEB and forget all about fidelity?”

The phase transition shows why that would change the complexity of the problem: in the strong-noise regime, XEB can stay high even when fidelity is exponentially small. And indeed, this discrepancy can be exploited by so-called spoofers for the XEB. These are efficient classical algorithms which can be used to succeed at a quantum advantage test even though they clearly do not achieve the intended advantage. These spoofers (Spoof1, Spoof2) can achieve high XEB scores comparable to those of the experiments and scaling like in the circuit depth for some constant .

Their basic idea is to introduce strong, judiciously chosen noise at specific circuit locations that has the effect of breaking up the simulation task up into smaller, much easier components, but at the same time still gives a high XEB score. In doing so, they exploit the strong-noise regime in which the XEB is a really bad proxy for the fidelity. This allows them to sample from states with exponentially low fidelity while achieving a high XEB value.

The discovery of the phase transition and the associated spoofers highlights the importance of modeling when assessing—and even formulating—the advantage claim based on noisy data.

But we can’t compute the XEB!

You might also be worried that the experiments did not actually compute the XEB in the advantage regime because to estimate it they would have needed to compute ideal probabilities—a task that is hard by definition of the advantage regime. Instead, they used a bunch of different ways to extrapolate the true XEB from XEB proxies (proxy of a proxy of the fidelity). Is this is a valid way of getting an estimate of the true XEB?

It totally is! Different extrapolations—from easy-to-simulate to hard-to-simulate, from small system to large system etc—all gave consistent answers for the experimental XEB value of the supremacy circuits. Think of this as having several lines that cross in the same point. For that crossing to be a coincidence, something crazy, conspiratorial must happen exactly when you move to the supremacy circuits from different directions. That is why it is reasonable to trust the reported value of the XEB.

That’s exactly how experiments work!

All of this is to say that establishing that the experiments correctly solved finite-fidelity RCS and therefore show quantum advantage involved a lot of experimental characterization of the noise as well as theoretical work to understand the effects of noise on the quantity we care about—the fidelity between the experimental and ideal states.

In this respect (and maybe also in the scale of the discovery), the quantum advantage experiments are similar to the recent experiments reporting discovery of the Higgs boson and gravitational waves. While I do not claim to understand any of the details, what I do understand is that in both experiments, there is an unfathomable amount of data that could not be interpreted without preselection and post-processing of the data, theories, extrapolations and approximations that model the experiment and measurement apparatus. All of those enter the respective smoking-gun plots that show the discoveries.

If you believe in the validity of experimental physics methodology, you should therefore also believe in the type of evidence underlying experimental claim of the quantum advantage demonstrations: that they sampled from the output distribution of a quantum state with the reported fidelities.

Put succinctly: If you believe in the Higgs boson and gravitational waves, you should probably also believe in the experimental demonstration of quantum advantage.

What are the counter-arguments?

The theoretical computer scientist

“The weak-noise limit is not physical. The appropriate scaling limit is one in which the local noise rate of the device is constant while the system size grows, and in that case, there is a classical simulation algorithm for RCS (SimIQP, SimRCS).”

In theoretical computer science, scaling of time or the system size in the input size is considered very natural: We say an algorithm is efficient if its runtime and space usage only depend polynomially on the input size.

But all scaling arguments are hypothetical concepts, and we only care about the scaling at relevant sizes. In the end, every scaling limit is going to hit the wall of physical reality—be it the amount of energy or human lifetime that limits the time of an algorithm, or the physical resources that are required to build larger and larger computers. To keep the scaling limit going as we increase the size of our computations, we need innovation that makes the components smaller and less noisy.

At the scales relevant to RCS, the scaling of the noise is benign and even natural. Why? Well, currently, the actual noise in quantum computers is not governed by the fundamental limit, but by engineering challenges. Realizing this limit therefore amounts to engineering improvements in the system size and noise rate that are achieved over time. Sure, at some point that scaling limit is also going to hit a fundamental barrier below which the noise cannot be improved. But we are surely far away from that limit, yet. What is more, already now logical qubits are starting to work and achieve beyond-breakeven fidelities. So even if the engineering improvements should flatten out from here onward, QEC will keep the noise limit going and even accelerate it in the intermediate future.

The complexity maniac

“All the hard complexity-theoretic evidence for quantum advantage is in the near-ideal regime, but now you are claiming advantage for the low-fidelity version of that task.”

This is probably the strongest counter-argument in my opinion, and I gave my best response above. Let me just add that this is a question about computational complexity. In the end, all of complexity theory is based on belief. The only real evidence we have for the hardness of any task is the absence of an efficient algorithm, or the reduction to a paradigmatic, well-studied task for which there is no efficient algorithm.

I am not sure how much I would bet that you cannot find an efficient algorithm for finite-fidelity RCS in the regime of the experiments, but it is certainly a pizza.

The enthusiastic skeptic

“There is no verification test that just depends on the classical samples, is efficient and does not make any assumptions about the device. In particular, you cannot unconditionally verify fidelity just from the classical samples. Why should I believe the data?”

Yes, sure, the current advantage demonstrations are not device-independent. But the comparison you should have in mind are Bell tests. The first proper Bell tests of Aspect and others in the 80s were not free of loopholes. They still allowed for contrived explanations of the data that did not violate local realism. Still, I can hardly believe that anyone would argue that Bell inequalities were not violated already back then.

As the years passed, these remaining loopholes were closed. To be a skeptic of the data, people needed to come up with more and more adversarial scenarios that could explain the data. We are working on the same to happen with quantum advantage demonstrations: come up with better schemes and better tests that require less and less assumptions or knowledge about the specifics of the device.

The “this is unfair” argument

“When you chose the gates and architecture of the circuit dependent on your device, you tailored the task too much to the device and that is unfair. Not even the different RCS experiments solve exactly the same task.”

This is not really an argument against the achievement of quantum advantage but more against the particular choices of circuit ensembles in the experiments. Sure, the specific computations solved are still somewhat tailored to the hardware itself and in this sense the experiments are not hardware-independent yet, but they still solve fine computational tasks. Moving away from such hardware-tailored task specifications is another important next step and we are working on it.

In the third and last part of this mini series I will address next steps in quantum advantage that aim at closing some of the remaining loopholes. The most important—and theoretically interesting—one is to enable efficient verification of quantum advantage using less or even no specific knowledge about the device that was used, but just the measurement outcomes.

References

(survey) Hangleiter, D. & Eisert, J. Computational advantage of quantum random sampling. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 035001 (2023).

(classSim1) Pan, F., Chen, K. & Zhang, P. Solving the sampling problem of the Sycamore quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 090502 (2022).

(classSim2) Kalachev, G., Panteleev, P., Zhou, P. & Yung, M.-H. Classical Sampling of Random Quantum Circuits with Bounded Fidelity. arXiv.2112.15083 (2021).

(WN) Dalzell, A. M., Hunter-Jones, N. & Brandão, F. G. S. L. Random Quantum Circuits Transform Local Noise into Global White Noise. Commun. Math. Phys. 405, 78 (2024).

(PT1)vMorvan, A. et al. Phase transitions in random circuit sampling. Nature 634, 328–333 (2024).

(PT2) Ware, B. et al. A sharp phase transition in linear cross-entropy benchmarking. arXiv:2305.04954 (2023).

(Spoof1) Barak, B., Chou, C.-N. & Gao, X. Spoofing Linear Cross-Entropy Benchmarking in Shallow Quantum Circuits. in 12th Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference (ITCS 2021) (ed. Lee, J. R.) vol. 185 30:1-30:20 (2021).

(Spoof2) Gao, X. et al. Limitations of Linear Cross-Entropy as a Measure for Quantum Advantage. PRX Quantum 5, 010334 (2024).

(SimIQP) Bremner, M. J., Montanaro, A. & Shepherd, D. J. Achieving quantum supremacy with sparse and noisy commuting quantum computations. Quantum 1, 8 (2017).

(SimRCS) Aharonov, D., Gao, X., Landau, Z., Liu, Y. & Vazirani, U. A polynomial-time classical algorithm for noisy random circuit sampling. in Proceedings of the 55th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing 945–957 (2023).