I felt like a yoyo.

I was standing in a hallway at the University of Maryland. On one side stood quantum-information theorists. On the other side stood statistical-mechanics scientists.* The groups eyed each other, like Jets and Sharks in West Side Story, except without fighting or dancing.

This March, the groups were generous enough to host me for a visit. I parked first at QuICS, the Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science. Established in October 2014, QuICS had moved into renovated offices the previous month. QuICSland boasts bright colors, sprawling armchairs, and the scent of novelty. So recently had QuICS arrived that the restroom had not acquired toilet paper (as I learned later than I’d have preferred).

From QuICS, I yoyo-ed to the chemistry building, where Chris Jarzynski’s group studies fluctuation relations. Fluctuation relations, introduced elsewhere on this blog, describe out-of-equilibrium systems. A system is out of equilibrium if large-scale properties of it change. Many systems operate out of equilibrium—boiling soup, combustion engines, hurricanes, and living creatures, for instance. Physicists want to describe nonequilibrium processes but have trouble: Living creatures are complicated. Hence the buzz about fluctuation relations.

My first Friday in Maryland, I presented a seminar about quantum voting for QuICS. The next Tuesday, I was to present about one-shot information theory for stat-mech enthusiasts. Each week, the stat-mech crowd invites its speaker to lunch. Chris Jarzynski recommended I invite QuICS. Hence the Jets-and-Sharks tableau.

“Have you interacted before?” I asked the hallway.

“No,” said a voice. QuICS hadn’t existed till last fall, and some QuICSers hadn’t had offices till the previous month.**

Silence.

“We’re QuICS,” volunteered Stephen Jordan, a quantum-computation theorist, “the Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science.”

So began the mingling. It continued at lunch, which we shared at three circular tables we’d dragged into a chain. The mingling continued during the seminar, as QuICSers sat with chemists, materials scientists, and control theorists. The mingling continued the next day, when QuICSer Alexey Gorshkov joined my discussion with the Jarzynski group. Back and forth we yoyo-ed, between buildings and topics.

“Mingled,” said Yigit Subasi. Yigit, a postdoc of Chris’s, specialized in quantum physics as a PhD student. I’d asked how he thinks about quantum fluctuation relations. Since Chris and colleagues ignited fluctuation-relation research, theorems have proliferated like vines in a jungle. Everyone and his aunty seems to have invented a fluctuation theorem. I canvassed Marylanders for bushwhacking tips.

Imagine, said Yigit, a system whose state you know. Imagine a gas, whose temperature you’ve measured, at equilibrium in a box. Or imagine a trapped ion. Begin with a state about which you have information.

Imagine performing work on the system “violently.” Compress the gas quickly, so the particles roil. Shine light on the ion. The system will leave equilibrium. “The information,” said Yigit, “gets mingled.”

Imagine halting the compression. Imagine switching off the light. Combine your information about the initial state with assumptions and physical laws.*** Manipulate equations in the right way, and the information might “unmingle.” You might capture properties of the violence in a fluctuation relation.

I’m grateful to have exchanged information in Maryland, to have yoyo-ed between groups. We have work to perform together. I have transformations to undergo.**** Let the unmingling begin.

With gratitude to Alexey Gorshkov and QuICS, and to Chris Jarzynski and the University of Maryland Department of Chemistry, for their hospitality, conversation, and camaraderie.

*Statistical mechanics is the study of systems that contain vast numbers of particles, like the air we breathe and white dwarf stars. I harp on about statistical mechanics often.

**Before QuICS’s birth, a future QuICSer had collaborated with a postdoc of Chris’s on combining quantum information with fluctuation relations.

***Yes, physical laws are assumptions. But they’re glorified assumptions.

****Hopefully nonviolent transformations.

al (direction flow of positively charged ions), then the electrons (negative charge carriers) are traveling in the opposite direction of the green arrow shown in the diagram. Referring to the diagram and using the right hand rule you can conclude a buildup of electrons at the long bottom edge of the Hall element running parallel to the longitudinal current, and an opposing positively charged edge at the long top edge of the Hall element. This separation of charge will produce a transverse potential difference and is labeled on the diagram as Hall voltage (VH). Once the electric force (acting towards the positively charged edge perpendicular to both current and magnetic field) from the charge build up balances with the Lorentz force (opposing the electric force), the result is a negative charge carrier with a straight line trajectory in the opposite direction of the green arrow. Essentially, Hall conductance is the longitudinal current divided by the Hall voltage.

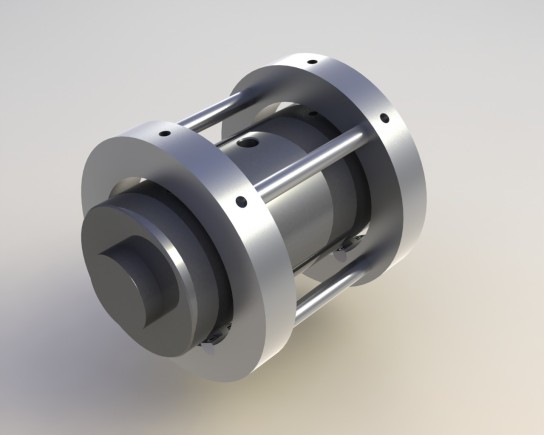

al (direction flow of positively charged ions), then the electrons (negative charge carriers) are traveling in the opposite direction of the green arrow shown in the diagram. Referring to the diagram and using the right hand rule you can conclude a buildup of electrons at the long bottom edge of the Hall element running parallel to the longitudinal current, and an opposing positively charged edge at the long top edge of the Hall element. This separation of charge will produce a transverse potential difference and is labeled on the diagram as Hall voltage (VH). Once the electric force (acting towards the positively charged edge perpendicular to both current and magnetic field) from the charge build up balances with the Lorentz force (opposing the electric force), the result is a negative charge carrier with a straight line trajectory in the opposite direction of the green arrow. Essentially, Hall conductance is the longitudinal current divided by the Hall voltage. t that will attempt to grow graphene in a unique way. My contribution included the set-up of the stepper motor (pictured to the right) and its controls, so that it would very slowly travel down the tube in an attempt to grow a long strip of graphene. If Caltech scientist David Boyd and graduate student Chen-Chih Hsu are able to grow the long strips of graphene, this will mark yet another landmark achievement for them and Caltech in graphene research, bringing all of us closer to technologies such as flexible electronics, synthetic nerve cells, 500-mile range Tesla cars and batteries that allow us to stream Netflix on smartphones for weeks on end.

t that will attempt to grow graphene in a unique way. My contribution included the set-up of the stepper motor (pictured to the right) and its controls, so that it would very slowly travel down the tube in an attempt to grow a long strip of graphene. If Caltech scientist David Boyd and graduate student Chen-Chih Hsu are able to grow the long strips of graphene, this will mark yet another landmark achievement for them and Caltech in graphene research, bringing all of us closer to technologies such as flexible electronics, synthetic nerve cells, 500-mile range Tesla cars and batteries that allow us to stream Netflix on smartphones for weeks on end.