We are now at an exciting point in our process of developing quantum computers and understanding their computational power: It has been demonstrated that quantum computers can outperform classical ones (if you buy my argument from Parts 1 and 2 of this mini series). And it has been demonstrated that quantum fault-tolerance is possible for at least a few logical qubits. Together, these form the elementary building blocks of useful quantum computing.

And yet: the devices we have seen so far are still nowhere near being useful for any advantageous application in, say, condensed-matter physics or quantum chemistry, which is where the promise of quantum computers lies.

So what is next in quantum advantage?

This is what this third and last part of my mini-series on the question “Has quantum advantage been achieved?” is about.

The 100 logical qubits regime

I want to have in mind the regime in which we have 100 well-functioning logical qubits, so 100 qubits on which we can run maybe 100 000 gates.

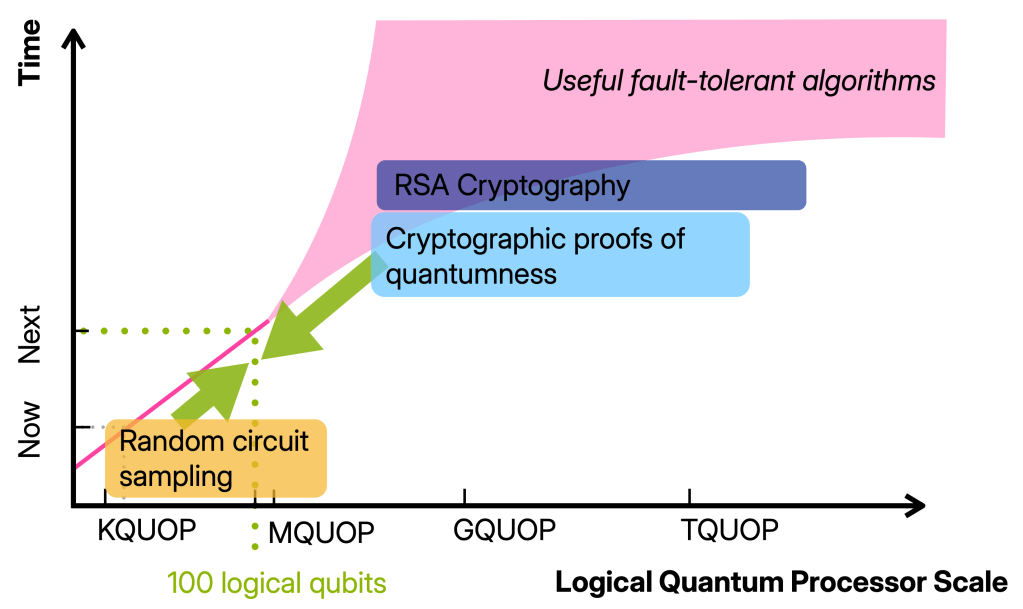

Building devices operating in this regime will require thousand(s) of physical qubits and is therefore well beyond the proof-of-principle quantum advantage and fault-tolerance experiments that have been done. At the same time, it is (so far) still one or more orders of magnitude away from any of the first applications such as simulating, say, the Fermi-Hubbard model or breaking cryptography. In other words, it is a qualitatively different regime from the early fault-tolerant computations we can do now. And yet, there is not a clear picture for what we can and should do with such devices.

The next milestone: classically verifiable quantum advantage

In this post, I want to argue that a key milestone we should aim for in the 100 logical qubit regime is classically verifiable quantum advantage. Achieving this will not only require the jump in quantum device capabilities but also finding advantage schemes that allow for classical verification using these limited resources.

Why is it an interesting and feasible goal and what is it anyway?

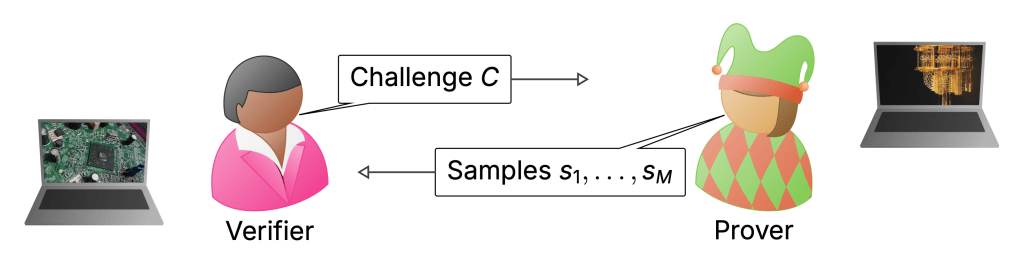

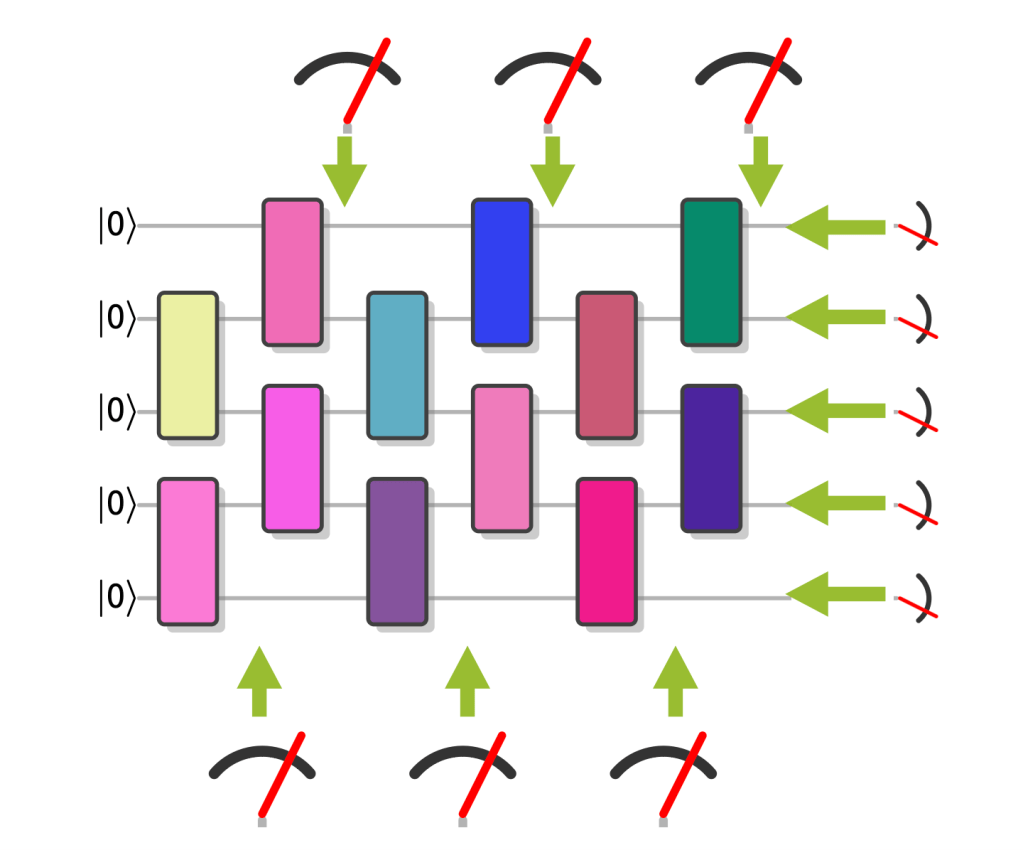

To my mind, the biggest weakness of the RCS experiments is the way they are verified. I discussed this extensively in the last posts—verification uses XEB which can be classically spoofed, and only actually measured in the simulatable regime. Really, in a quantum advantage experiment I would want there to be an efficient procedure that will without any reasonable doubt convince us that a computation must have been performed by a quantum computer when we run it. In what I think of as classically verifiable quantum advantage, a (classical) verifier would come up with challenge circuits which they would then send to a quantum server. These would be designed in such a way that once the server returns classical samples from those circuits, the verifier can convince herself that the server must have run a quantum computation.

This is the jump from a physics-type experiment (the sense in which advantage has been achieved) to a secure protocol that can be used in settings where I do not want to trust the server and the data it provides me with. Such security may also allow a first application of quantum computers: to generate random numbers whose genuine randomness can be certified—a task that is impossible classically.

Here is the problem: On the one hand, we do know of schemes that allow us to classically verify that a computer is quantum and generate random numbers, so called cryptographic proofs of quantumness (PoQ). A proof of quantumness is a highly reliable scheme in that its security relies on well-established cryptography. Their big drawback is that they require a large number of qubits and operations, comparable to the resources required for factoring. On the other hand, the computations we can run in the advantage regime—basically, random circuits—are very resource-efficient but not verifiable.

The 100-logical-qubit regime lies right in the middle, and it seems more than plausible that classically verifiable advantage is possible in this regime. The theory challenge ahead of us is to find it: a quantum advantage scheme that is very resource-efficient like RCS and also classically verifiable like proofs of quantumness.

With this in mind, let me spell out some concrete goals that we can achieve using 100 logical qubits on the road to classically verifiable quantum advantage.

1. Demonstrate fault-tolerant quantum advantage

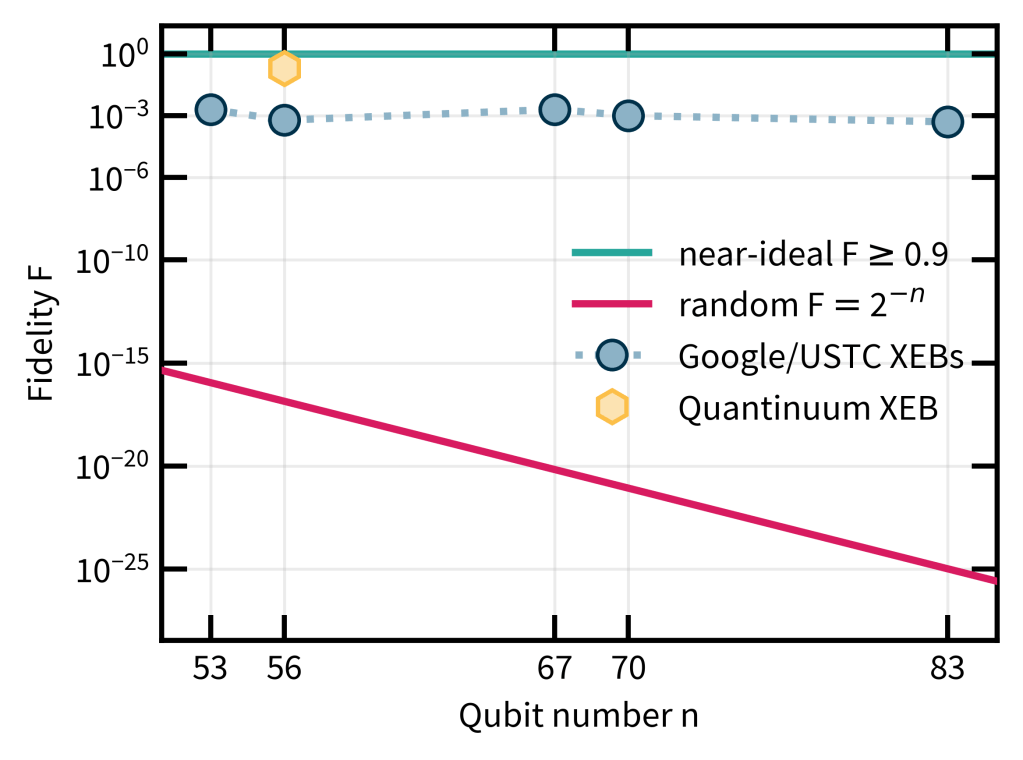

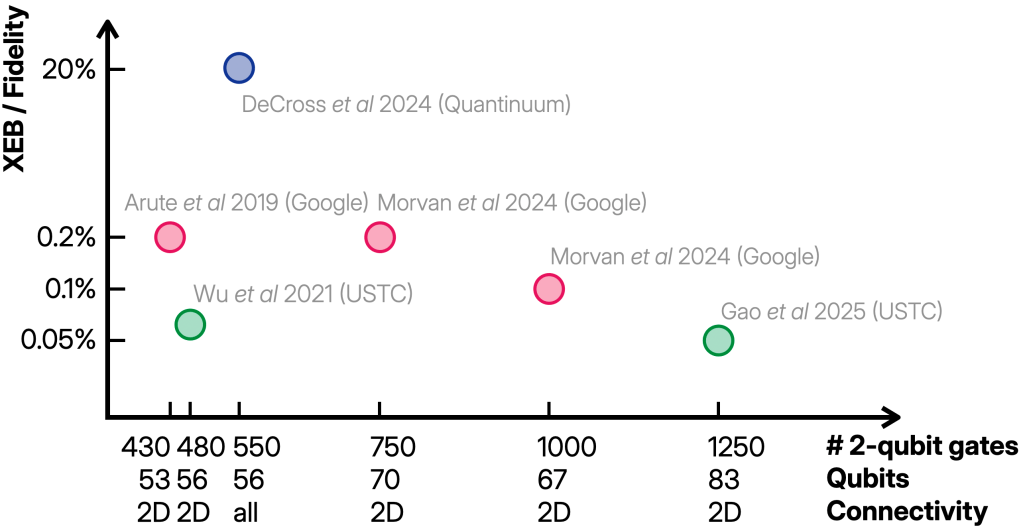

Before we talk about verifiable advantage, the first experiment I would like to see is one that combines the two big achievements of the past years, and shows that quantum advantage and fault-tolerance can be achieved simultaneously. Such an experiment would be similar in type to the RCS experiments, but run on encoded qubits with gate sets that match that encoding. During the computation, noise would be suppressed by correcting for errors using the code. In doing so, we could reach the near-perfect regime of RCS as opposed to the finite-fidelity regime that current RCS experiments operate in (as I discussed in detail in Part 2).

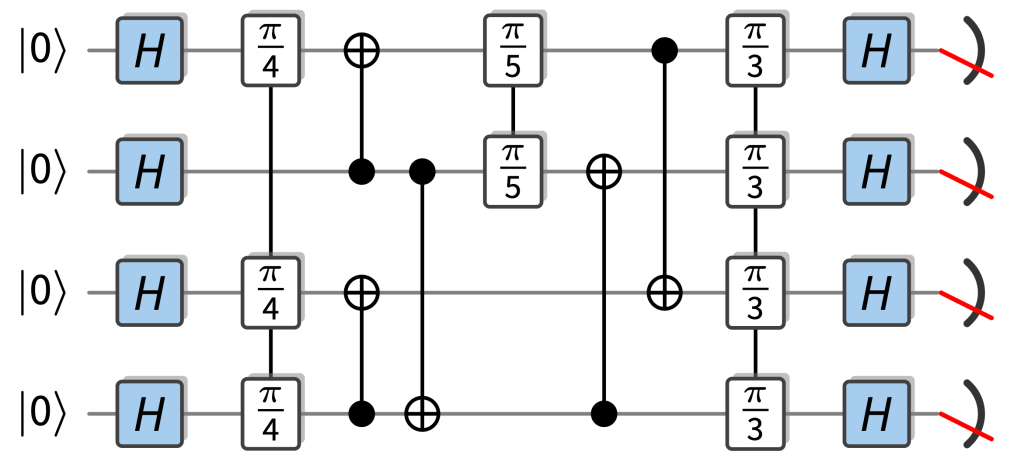

Random circuits with a quantum advantage that are particularly easy to implement fault-tolerantly are so-called IQP circuits. In those circuits, the gates are controlled-NOT gates and diagonal gates, so rotations , which just add a phase to a basis state as . The only “quantumness” comes from the fact that each input qubit is in the superposition state , and that all qubits are measured in the basis. This is an example of an example of an IQP circuit:

As it so happens, IQP circuits are already really well understood since one of the first proposals for quantum advantage was based on IQP circuits (VerIQP1), and for a lot of the results in random circuits, we have precursors for IQP circuits, in particular, their ideal and noisy complexity (SimIQP). This is because their near-classical structure makes them relatively easy to study. Most importantly, their outcome probabilities are simple (but exponentially large) sums over phases that can just be read off from which gates are applied in the circuit and we can use well-established classical techniques like Boolean analysis and coding theory to understand those.

IQP gates are natural for fault-tolerance because there are codes in which all the operations involved can be implemented transversally. This means that they only require parallel physical single- or two-qubit gates to implement a logical gate rather than complicated fault-tolerant protocols which are required for universal circuits. This is in stark contrast to universal circuit which require resource-intensive fault-tolerant protocols. Running computations with IQP circuits would also be a step towards running real computations in that they can involve structured components such as cascades of CNOT gates and the like. These show up all over fault-tolerant constructions of algorithmic primitives such as arithmetic or phase estimation circuits.

Our concrete proposal for an IQP-based fault-tolerant quantum advantage experiment in reconfigurable-atom arrays is based on interleaving diagonal gates and CNOT gates to achieve super-fast scrambling (ftIQP1). A medium-size version of this protocol was implemented by the Harvard group (LogicalExp) but with only a bit more effort, it could be performed in the advantage regime.

In those proposals, verification will still suffer from the same problems of standard RCS experiments, so what’s up next is to fix that!

2. Closing the verification loophole

I said that a key milestone for the 100-logical-qubit regime is to find schemes that lie in between RCS and proofs of quantumness in terms of their resource requirements but at the same time allow for more efficient and more convincing verification than RCS. Naturally, there are two ways to approach this space—we can make quantum advantage schemes more verifiable, and we can make proofs of quantumness more resource-efficient.

First, let’s focus on the former approach and set a more moderate goal than full-on classical verification of data from an untrusted server. Are there variants of RCS that allow us to efficiently verify that finite-fidelity RCS has been achieved if we trust the experimenter and the data they hand us?

2.1 Efficient quantum verification using random circuits with symmetries

Indeed, there are! I like to think of the schemes that achieve this as random circuits with symmetries. A symmetry is an operator such that the outcome state of the computation (or some intermediate state) is invariant under the symmetry, so . The idea is then to find circuits that exhibit a quantum advantage and at the same time have symmetries that can be easily measured, say, using only single-qubit measurements or a single gate layer. Then, we can use these measurements to check whether or not the pre-measurement state respects the symmetries. This is a test for whether the quantum computer prepared the correct state, because errors or deviations from the true state would violate the symmetry (unless they were adversarially engineered).

In random circuits with symmetries, we can thus use small, well-characterized measurements whose outcomes we trust to probe whether a large quantum circuit has been run correctly. This is possible in a scenario I call the trusted experimenter scenario.

The trusted experimenter scenario

In this scenario, we receive data from an actual experiment in which we trust that certain measurements were actually and correctly performed.

Here are some examples of random circuits with symmetries, which allow for efficient verification of quantum advantage in the trusted experimenter scenario.

Graph states. My first example are locally rotated graph states (GStates). These are states that are prepared by CZ gates acting according to the edges of a graph on an initial all- state, and a layer of single-qubit -rotations is performed before a measurement in the basis. (Yes, this is also an IQP circuit.) The symmetries of this circuit are locally rotated Pauli operators, and can therefore be measured using only single-qubit rotations and measurements. What is more, these symmetries fully determine the graph state. Determining the fidelity then just amounts to averaging the expectation values of the symmetries, which is so efficient you can even do it in your head. In this example, we need measuring the outcome state to obtain hard-to-reproduce samples and measuring the symmetries are done in two different (single-qubit) bases.

With 100 logical qubits, samples from classically intractable graph states on several 100 qubits could be easily generated.

Bell sampling. The drawback of this approach is that we need to make two different measurements for verification and sampling. But it would be much more neat if we could just verify the correctness of a set of classically hard samples by only using those samples. For an example where this is possible, consider two copies of the output state of a random circuit, so . This state is invariant under a swap of the two copies, and in fact the expectation value of the SWAP operator in a noisy state preparation of determines the purity of the state, so . It turns out that measuring all pairs of qubits in the state in the pairwise basis of the four Bell states , where is one of the four Pauli matrices , this is hard to simulate classically (BellSamp). You may also observe that the SWAP operator is diagonal in the Bell basis, so its expectation value can be extracted from the Bell-basis measurements—our hard to simulate samples. To do this, we just average sign assignments to the samples according to their parity.

If the circuit is random, then under the same assumptions as those used in XEB for random circuits, the purity is a good estimator of the fidelity, so . So here is an example, where efficient verification is possible directly from hard-to-simulate classical samples under the same assumptions as those used to argue that XEB equals fidelity.

With 100 logical qubits, we can achieve quantum advantage which is at least as hard as the current RCS experiments that can also be efficiently (physics-)verified from the classical data.

Fault-tolerant circuits. Finally, suppose that we run a fault-tolerant quantum advantage experiment. Then, there is a natural set of symmetries of the state at any point in the circuit, namely, the stabilizers of the code we use. In a fault-tolerant experiment we repeatedly measure those stabilizers mid-circuit, so why not use that data to assess the quality of the logical state? Indeed, it turns out that the logical fidelity can be estimated efficiently from stabilizer expectation values even in situations in which the logical circuit has a quantum advantage (SyndFid).

With 100 logical qubits, we could therefore just run fault-tolerant IQP circuits in the advantage regime (ftIQP1) and the syndrome data would allow us to estimate the logical fidelity.

In all of these examples of random circuits with symmetries, coming up with classical samples that pass the verification tests is very easy, so the trusted-experimenter scenario is crucial for this to work. (Note, however, that it may be possible to add tests to Bell sampling that make spoofing difficult.) At the same time, these proposals are very resource-efficient in that they only increase the cost of a pure random-circuit experiment by a relatively small amount. What is more, the required circuits have more structure than random circuits in that they typically require gates that are natural in fault-tolerant implementations of quantum algorithms.

Performing random circuit sampling with symmetries is therefore a natural next step en-route to both classically verifiable advantage that closes the no-efficient verification loophole, and towards implementing actual algorithms.

What if we do not want to afford that level of trust in the person who runs the quantum circuit, however?

2.2 Classical verification using random circuits with planted secrets

If we do not trust the experimenter, we are in the untrusted quantum server scenario.

The untrusted quantum server scenario

In this scenario, we delegate a quantum computation to an untrusted (presumably remote) quantum server—think of using a Google or Amazon cloud server to run your computation. We can communicate with this server using classical information.

In the untrusted server scenario, we can hope to use ideas from proofs of quantumness such as the use of classical cryptography to design families of quantum circuits in which some secret structure is planted. This secret structure should give the verifier a way to check whether a set of samples passes a certain verification test. At the same time it should not be detectable, or at least not be identifiable from the circuit description alone.

The simplest example of such secret structure could be a large peak in an otherwise flat output distribution of a random-looking quantum circuit. To do this, the verifier would pick a (random) string and design a circuit such that the probability of seeing in samples, is large. If the peak is hidden well, finding it just from the circuit description would require searching through all of the outcome bit strings and even just determining one of the outcome probabilities is exponentially difficult. A classical spoofer trying to fake the samples from a quantum computer would then be caught immediately: the list of samples they hand the verifier will not even contain unless they are unbelievably lucky, since there are exponentially many possible choices of .

Unfortunately, planting such secrets seems to be very difficult using universal circuits, since the output distributions are so unstructured. This is why we have not yet found good candidates of circuits with peaks, but some tries have been made (Peaks,ECPeaks,HPeaks)

We do have a promising candidate, though—IQP circuits! The fact that the output distributions of IQP circuits are quite simple could very well help us design sampling schemes with hidden secrets. Indeed, the idea of hiding peaks has been pioneered by Shepherd and Bremner (VerIQP1) who found a way to design classically hard IQP circuits with a large hidden Fourier coefficient. The presence of this large Fourier coefficient can easily be checked from a few classical samples, and random IQP circuits do not have any large Fourier coefficients. Unfortunately, for that construction and a variation thereof (VerIQP2), it turned out that the large coefficient can be detected quite easily from the circuit description (ClassIQP1,ClassIQP2).

To this day, it remains an exciting open question whether secrets can be planted in (maybe IQP) circuit families in a way that allows for efficient classical verification. Even finding a scheme with some large gap between verification and simulation times would be exciting, because it would for the first time allow us to verify a quantum computing experiment in the advantage regime using only classical computation.

Towards applications: certifiable random number generation

Beyond verified quantum advantage, sampling schemes with hidden secrets may be usable to generate classically certifiable random numbers: You sample from the output distribution of a random circuit with a planted secret, and verify that the samples come from the correct distribution using the secret. If the distribution has sufficiently high entropy, truly random numbers can be extracted from them. The same can be done for RCS, except that some acrobatics are needed to get around the problem that verification is just as costly as simulation (CertRand, CertRandExp). Again, a large gap between verification and simulation times would probably permit such certified random number generation.

The goal here is firstly a theoretical one: Come up with a planted-secret RCS scheme that has a large verification-simulation gap. But then, of course, it is an experimental one: actually perform such an experiment to classically verify quantum advantage.

Should an IQP-based scheme of circuits with secrets exist, 100 logical qubits is the regime where it should give a relevant advantage.

Three milestones

Altogether, I proposed three milestones for the 100 logical qubit regime.

- Perform fault-tolerant quantum advantage using random IQP circuits. This will allow an improvement of the fidelity towards performing near-perfect RCS and thus closes the scalability worries of noisy quantum advantage I discussed in my last post.

- Perform RCS with symmetries. This will allow for efficient verification of quantum advantage in the trusted experimenter scenario and thus make a first step toward closing the verification loophole.

- Find and perform RCS schemes with planted secrets. This will allow us to verify quantum advantage in the remote untrusted server scenario and presumably give a first useful application of quantum computers to generate classically certified random numbers.

All of these experiments are natural steps towards performing actually useful quantum algorithms in that they use more structured circuits than just random universal circuits and can be used to benchmark the performance of the quantum devices in an advantage regime. Moreover, all of them close some loophole of the previous quantum advantage demonstrations, just like follow-up experiments to the first Bell tests have closed the loopholes one by one.

I argued that IQP circuits will play an important role in achieving those milestones since they are a natural circuit family in fault-tolerant constructions and promising candidates for random circuit constructions with planted secrets. Developing a better understanding of the properties of the output distributions of IQP circuits will help us achieve the theory challenges ahead.

Experimentally, the 100 logical qubit regime is exactly the regime to shoot for with those circuits since while IQP circuits are somewhat easier to simulate than universal random circuits, 100 qubits is well in the classically intractable regime.

What I did not talk about

Let me close this mini-series by touching on a few things that I would have liked to discuss more.

First, there is the OTOC experiment by the Google team (OTOC) which has spawned quite a debate. This experiment claims to achieve quantum advantage for an arguably more natural task than sampling, namely, computing expectation values. Computing expectation values is at the heart of quantum-chemistry and condensed-matter applications of quantum computers. And it has the nice property that it is what the Google team called “quantum-verifiable” (and what I would call “hopefully-in-the-future-verifiable”) in the following sense: Suppose we perform an experiment to measure a classically hard expectation value on a noisy device now, and suppose this expectation value actually carries some signal, so it is significantly far away from zero. Once we have a trustworthy quantum computer in the future, we will be able to check that the outcome of this experiment was correct and hence quantum advantage was achieved. There is a lot of interesting science to discuss about the details of this experiment and maybe I will do so in a future post.

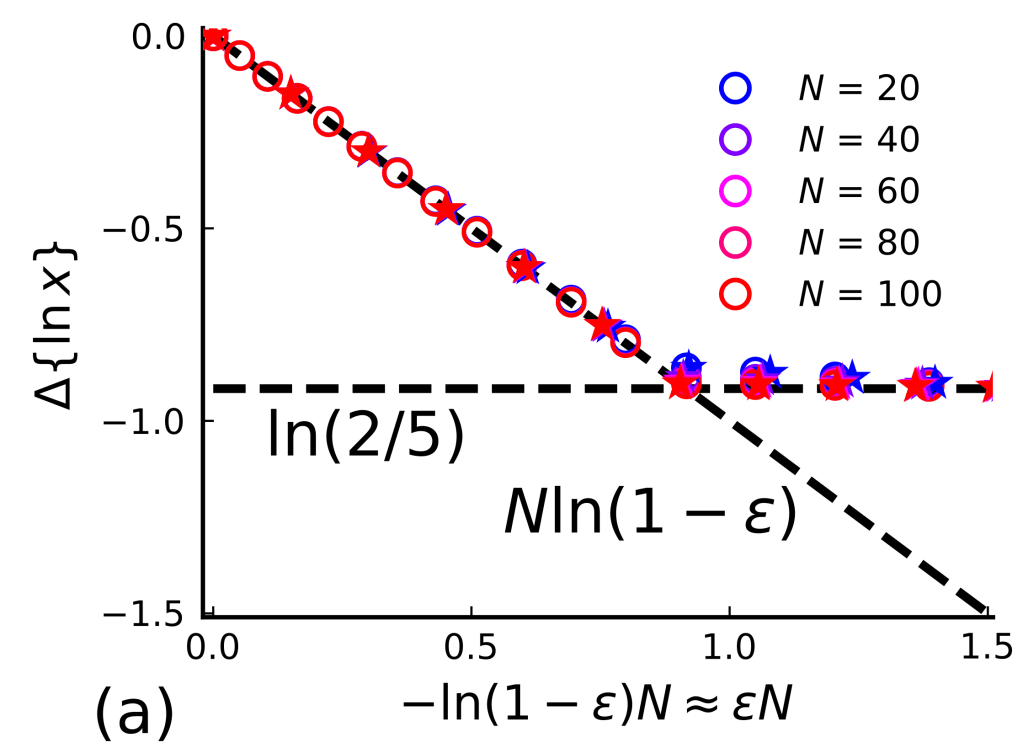

Finally, I want to mention an interesting theory challenge that relates to the noise-scaling arguments I discussed in detail in Part 2: The challenge is to understand whether quantum advantage can be achieved in the presence of a constant amount of local noise. What do we know about this? On the one hand, log-depth random circuits with constant local noise are easy to simulate classically (SimIQP,SimRCS), and we have good numerical evidence that random circuits at very low depths are easy to simulate classically even without noise (LowDSim). So is there a depth regime in between the very low depth and the log-depth regime in which quantum advantage persists under constant local noise? Is this maybe even true in a noise regime that does not permit fault-tolerance (see this interesting talk)? In the regime in which fault-tolerance is possible, it turns out that one can construct simple fault-tolerance schemes that do not require any quantum feedback, so there are distributions that are hard to simulate classically even in the presence of constant local noise.

So long, and thanks for all the fish!

I hope that in this mini-series I could convince you that quantum advantage has been achieved. There are some open loopholes but if you are happy with physics-level experimental evidence, then you should be convinced that the RCS experiments of the past years have demonstrated quantum advantage.

As the devices are getting better at a rapid pace, there is a clear goal that I hope will be achieved in the 100-logical-qubit regime: demonstrate fault-tolerant and verifiable advantage (for the experimentalists) and come up with the schemes to do that (for the theorists)! Those experiments would close the loopholes of the current RCS experiments. And they would work as a stepping stone towards actual algorithms in the advantage regime.

I want to end with a huge thanks to Spiros Michalakis, John Preskill and Frederik Hahn who have patiently read and helped me improve these posts!

References

Fault-tolerant quantum advantage

(ftIQP1) Hangleiter, D. et al. Fault-Tolerant Compiling of Classically Hard Instantaneous Quantum Polynomial Circuits on Hypercubes. PRX Quantum 6, 020338 (2025).

(LogicalExp) Bluvstein, D. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 626, 58–65 (2024).

Random circuits with symmetries

(BellSamp) Hangleiter, D. & Gullans, M. J. Bell Sampling from Quantum Circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 020601 (2024).

(GStates) Ringbauer, M. et al. Verifiable measurement-based quantum random sampling with trapped ions. Nat Commun 16, 1–9 (2025).

(SyndFid) Xiao, X., Hangleiter, D., Bluvstein, D., Lukin, M. D. & Gullans, M. J. In-situ benchmarking of fault-tolerant quantum circuits.

I. Clifford circuits. arXiv:2601.21472

II. Circuits with a quantum advantage. (coming soon!)

Verification with planted secrets

(PoQ) Brakerski, Z., Christiano, P., Mahadev, U., Vazirani, U. & Vidick, T. A Cryptographic Test of Quantumness and Certifiable Randomness from a Single Quantum Device. in 2018 IEEE 59th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS) 320–331 (2018).

(VerIQP1) Shepherd, D. & Bremner, M. J. Temporally unstructured quantum computation. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 465, 1413–1439 (2009).

(VerIQP2) Bremner, M. J., Cheng, B. & Ji, Z. Instantaneous Quantum Polynomial-Time Sampling and Verifiable Quantum Advantage: Stabilizer Scheme and Classical Security. PRX Quantum 6, 020315 (2025).

(ClassIQP1) Kahanamoku-Meyer, G. D. Forging quantum data: classically defeating an IQP-based quantum test. Quantum 7, 1107 (2023).

(ClassIQP2) Gross, D. & Hangleiter, D. Secret-Extraction Attacks against Obfuscated Instantaneous Quantum Polynomial-Time Circuits. PRX Quantum 6, 020314 (2025).

(Peaks) Aaronson, S. & Zhang, Y. On verifiable quantum advantage with peaked circuit sampling. arXiv:2404.14493

(ECPeaks) Deshpande, A., Fefferman, B., Ghosh, S., Gullans, M. & Hangleiter, D. Peaked quantum advantage using error correction. arXiv:2510.05262

(HPeaks) Gharibyan, H. et al. Heuristic Quantum Advantage with Peaked Circuits. arXiv:2510.25838

Certifiable random numbers

(CertRand) Aaronson, S. & Hung, S.-H. Certified Randomness from Quantum Supremacy. in Proceedings of the 55th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing 933–944 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2023).

(CertRandExp) Liu, M. et al. Certified randomness amplification by dynamically probing remote random quantum states. arXiv:2511.03686

OTOC

(OTOC) Abanin, D. A. et al. Observation of constructive interference at the edge of quantum ergodicity. Nature 646, 825–830 (2025).

Noisy complexity

(SimIQP) Bremner, M. J., Montanaro, A. & Shepherd, D. J. Achieving quantum supremacy with sparse and noisy commuting quantum computations. Quantum 1, 8 (2017).

(SimRCS) Aharonov, D., Gao, X., Landau, Z., Liu, Y. & Vazirani, U. A polynomial-time classical algorithm for noisy random circuit sampling. in Proceedings of the 55th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing 945–957 (2023).

(LowDSim) Napp, J. C., La Placa, R. L., Dalzell, A. M., Brandão, F. G. S. L. & Harrow, A. W. Efficient Classical Simulation of Random Shallow 2D Quantum Circuits. Phys. Rev. X 12, 021021 (2022).