In anticipation of The Theory of Everything which comes out today, and in the spirit of continuing with Quantum Frontiers’ current movie theme, I wanted to provide an overview of Stephen Hawking’s pathbreaking research. Or at least to the best of my ability—not every blogger on this site has won bets against Hawking! In particular, I want to describe Hawking’s work during the late ‘60s and through the ’70s. His work during the ’60s is the backdrop for this movie and his work during the ’70s revolutionized our understanding of black holes.

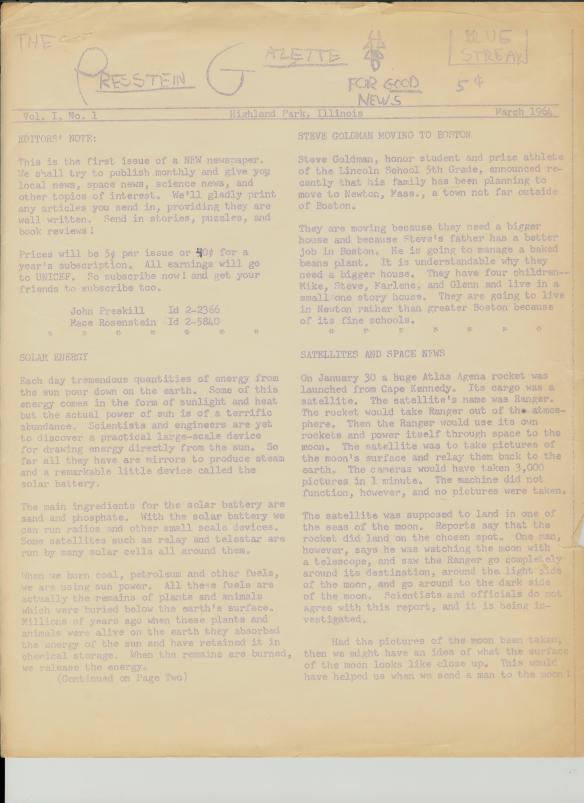

(Portrait of Stephen Hawking outside the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, Cambridge. Credit: Jason Bye)

As additional context, this movie is coming out at a fascinating time, at a time when Hawking’s contributions appear more prescient and important than ever before. I’m alluding to the firewall paradox, which is the modern reincarnation of the information paradox (which will be discussed below), and which this blog has discussed multiple times. Progress through paradox is an important motto in physics and Hawking has been at the center of arguably the most challenging paradox of the past half century. I should also mention that despite irresponsible journalism in response to Hawking’s “there are no black holes” comment back in January, that there is extremely solid evidence that black holes do in fact exist. Hawking was referring to a technical distinction concerning the horizon/boundary of black holes.

Now let’s jump back and imagine that we are all young graduate students at Cambridge in the early ‘60s. Our protagonist, a young Hawking, had recently been diagnosed with ALS, he had recently met Jane Wilde and he was looking for a thesis topic. This was an exciting time for Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity (GR). The gravitational redshift had recently been confirmed by Pound and Rebka at Harvard, which put the theory on extremely solid footing. This was the third of three “classical tests of GR.” So now that everyone was truly convinced that GR is correct, it became important to get serious about investigating its most bizarre predictions. Hawking and Penrose picked up on this theme most notably.The mathematics of GR allows for singularities which lead to things like the big bang and black holes. This mathematical possibility was known since the works of Friedmann, Lemaitre and Oppenheimer+Snyder starting all the way back in the 1920s, but these calculations involved unphysical assumptions—usually involving unrealistic symmetries. Hawking and Penrose each asked (and answered) the questions: how robust and generic are these mathematical singularities? Will they persist even if we get rid of assumptions like perfect spherical symmetry of matter? What is their interpretation in physics?

I know that I have now used the word “singularity” multiple times without defining it. However, this is for good reason—it’s very hard to assign a precise definition to the term! Some examples of singularities include regions of “infinite curvature” or with “conical deficits.”

Singularity theorems applied to cosmology: Hawking’s first major results, starting with his thesis in 1965, was proving that singularities on the cosmological scale—such as the big bang—were indeed generic phenomena and not just mathematical artifacts. This work was published immediately after, and it built upon, a seminal paper by Penrose. Also, I apologize for copping-out again, but it’s outside the scope of this post to say more about the big bang, but as a rough heuristic, imagine that if you run time backwards then you obtain regions of infinite density. Hawking and Penrose spent the next five or so years stripping away as many assumptions as they could until they were left with rather general singularity theorems. Essentially, they used MATH to say something exceptionally profound about THE BEGINNING OF THE UNIVERSE! Namely that if you start with any solution to Einstein’s equations which is consistent with our observed universe, and run the solution backwards, then you will obtain singularities (regions of infinite density at the Big Bang in this case)! However, I should mention that despite being a revolutionary leap in our understanding of cosmology, this isn’t the end of the story, and that Hawking has also pioneered an attempt to understand what happens when you add quantum effects to the mix. This is still a very active area of research.

Singularity theorems applied to black holes: the first convincing evidence for the existence of astrophysical black holes didn’t come until 1972 with the discovery of Cygnus X-1, and even this discovery was wrought with controversy. So imagine yourself as Hawking back in the late ’60s. He and Penrose had this powerful machinery which they had successfully applied to better understand THE BEGINNING OF THE UNIVERSE but there was still a question about whether or not black holes actually existed in nature (not just in mathematical fantasy land.) In the very late ‘60s and early ’70s, Hawking, Penrose, Carter and others convincingly argued that black holes should exist. Again, they used math to say something about how the most bizarre corners of the universe should behave–and then black holes were discovered observationally a few years later. Math for the win!

No hair theorem: after convincing himself that black holes exist Hawking continued his theoretical studies about their strange properties. In the early ’70s, Hawking, Carter, Israel and Robinson proved a very deep and surprising conjecture of John Wheeler–that black holes have no hair! This name isn’t the most descriptive but it’s certainly provocative. More specifically they showed that only a short time after forming, a black hole is completely described by only a few pieces of data: knowledge of its position, mass, charge, angular momentum and linear momentum (X, M, Q, J and L). It only takes a few dozen numbers to describe an exceptionally complicated object. Contrast this to, for example, 1000 dust particles where you would need tens of thousands of datum (the position and momentum of each particle, their charge, their mass, etc.) This is crazy, the number of degrees of freedom seems to decrease as objects form into black holes?

Black hole thermodynamics: around the same time, Carter, Hawking and Bardeen proved a result similar to the second law of thermodynamics (it’s debatable how realistic their assumptions are.) Recall that this is the law where “the entropy in a closed system only increases.” Hawking showed that, if only GR is taken into account, then the area of a black holes’ horizon only increases. This includes that if two black holes with areas and

merge then the new area

will be bigger than the sum of the original areas

.

Combining this with the no hair theorem led to a fascinating exploration of a connection between thermodynamics and black holes. Recall that thermodynamics was mainly worked out in the 1800s and it is very much a “classical theory”–one that didn’t involve either quantum mechanics or general relativity. The study of thermodynamics resulted in the thrilling realization that it could be summarized by four laws. Hawking and friends took the black hole connection seriously and conjectured that there would also be four laws of black hole mechanics.

In my opinion, the most interesting results came from trying to understand the entropy of black hole. The entropy is usually the logarithm of the number of possible states consistent with observed ‘large scale quantities’. Take the ocean for example, the entropy is humungous. There are an unbelievable number of small changes that could be made (imagine the number of ways of swapping the location of a water molecule and a grain of sand) which would be consistent with its large scale properties like it’s temperature. However, because of the no hair theorem, it appears that the entropy of a black hole is very small? What happens when some matter with a large amount of entropy falls into a black hole? Does this lead to a violation of the second law of thermodynamics? No! It leads to a generalization! Bekenstein, Hawking and others showed that there are two contributions to the entropy in the universe: the standard 1800s version of entropy associated to matter configurations, but also contributions proportional to the area of black hole horizons. When you add all of these up, a new “generalized second law of thermodynamics” emerges. Continuing to take this thermodynamic argument seriously (dE=TdS specifically), it appeared that black holes have a temperature!

As a quick aside, a deep and interesting question is what degrees of freedom contribute to this black hole entropy? In the late ’90s Strominger and Vafa made exceptional progress towards answering this question when he showed that in certain settings, the number of microstates coming from string theory exactly reproduces the correct black hole entropy.

Black holes evaporate (Hawking Radiation): again, continuing to take this thermodynamic connection seriously, if black holes have a temperature then they should radiate away energy. But what is the mechanism behind this? This is when Hawking fearlessly embarked on one of the most heroic calculations of the 20th century in which he slogged through extremely technical calculations involving “quantum mechanics in a curved space” and showed that after superimposing quantum effects on top of general relativity, there is a mechanism for particles to escape from a black hole.

This is obviously a hard thing to describe, but for a hack-job analogy, imagine you have a hot plate in a cool room. Somehow the plate “radiates” away its energy until it has the same temperature as the room. How does it do this? By definition, the reason why a plate is hot, is because its molecules are jiggling around rapidly. At the boundary of the plate, sometimes a slow moving air molecule (lower temperature) gets whacked by a molecule in the plate and leaves with a higher momentum than it started with, and in return the corresponding molecule in the plate loses energy. After this happens an enormous number of times, the temperatures equilibrate. In the context of black holes, these boundary interactions would never happen without quantum mechanics. General relativity predicts that anything inside the event horizon is causally disconnected from anything on the outside and that’s that. However, if you take quantum effects into account, then for some very technical reasons, energy can be exchanged at the horizon (interface between the “inside” and “outside” of the black hole.)

Black hole information paradox: but wait, there’s more! These calculations weren’t done using a completely accurate theory of nature (we use the phrase “quantum gravity” as a placeholder for whatever this theory will one day be.) They were done using some nightmarish amalgamation of GR and quantum mechanics. Seminal thought experiments by Hawking led to different predictions depending upon which theory one trusted more: GR or quantum mechanics. Most famously, the information paradox considered what would happen if an “encyclopedia” were thrown into the black hole. GR predicts that after the black hole has fully evaporated, such that only empty space is left behind, that the “information” contained within this encyclopedia would be destroyed. (To readers who know quantum mechanics, replace “encylopedia” with “pure state”.) This prediction unacceptably violates the assumptions of quantum mechanics, which predict that the information contained within the encyclopedia will never be destroyed. (Maybe imagine you enclosed the black hole with perfect sensing technology and measured every photon that came out of the black hole. In principle, according to quantum mechanics, you should be able to reconstruct what was initially thrown into the black hole.)

Making all of this more rigorous: Hawking spent most of the rest of the ’70s making all of this more rigorous and stripping away assumptions. One particularly otherworldly and powerful tool involved redoing many of these black hole calculations using the euclidean path integral formalism.

I’m certain that I missed some key contributions and collaborators in this short history, and I sincerely apologize for that. However, I hope that after reading this you have a deepened appreciation for how productive Hawking was during this period. He was one of humanity’s earliest pioneers into the uncharted territory that we call quantum gravity. And he has inspired at least a few generations worth of theoretical physicists, obviously, including myself.

In addition to reading many of Hawking’s original papers, an extremely fun source for this post is a book which was published after his 60th birthday conference.

al (direction flow of positively charged ions), then the electrons (negative charge carriers) are traveling in the opposite direction of the green arrow shown in the diagram. Referring to the diagram and using the right hand rule you can conclude a buildup of electrons at the long bottom edge of the Hall element running parallel to the longitudinal current, and an opposing positively charged edge at the long top edge of the Hall element. This separation of charge will produce a transverse potential difference and is labeled on the diagram as Hall voltage (VH). Once the electric force (acting towards the positively charged edge perpendicular to both current and magnetic field) from the charge build up balances with the Lorentz force (opposing the electric force), the result is a negative charge carrier with a straight line trajectory in the opposite direction of the green arrow. Essentially, Hall conductance is the longitudinal current divided by the Hall voltage.

al (direction flow of positively charged ions), then the electrons (negative charge carriers) are traveling in the opposite direction of the green arrow shown in the diagram. Referring to the diagram and using the right hand rule you can conclude a buildup of electrons at the long bottom edge of the Hall element running parallel to the longitudinal current, and an opposing positively charged edge at the long top edge of the Hall element. This separation of charge will produce a transverse potential difference and is labeled on the diagram as Hall voltage (VH). Once the electric force (acting towards the positively charged edge perpendicular to both current and magnetic field) from the charge build up balances with the Lorentz force (opposing the electric force), the result is a negative charge carrier with a straight line trajectory in the opposite direction of the green arrow. Essentially, Hall conductance is the longitudinal current divided by the Hall voltage. t that will attempt to grow graphene in a unique way. My contribution included the set-up of the stepper motor (pictured to the right) and its controls, so that it would very slowly travel down the tube in an attempt to grow a long strip of graphene. If Caltech scientist David Boyd and graduate student Chen-Chih Hsu are able to grow the long strips of graphene, this will mark yet another landmark achievement for them and Caltech in graphene research, bringing all of us closer to technologies such as flexible electronics, synthetic nerve cells, 500-mile range Tesla cars and batteries that allow us to stream Netflix on smartphones for weeks on end.

t that will attempt to grow graphene in a unique way. My contribution included the set-up of the stepper motor (pictured to the right) and its controls, so that it would very slowly travel down the tube in an attempt to grow a long strip of graphene. If Caltech scientist David Boyd and graduate student Chen-Chih Hsu are able to grow the long strips of graphene, this will mark yet another landmark achievement for them and Caltech in graphene research, bringing all of us closer to technologies such as flexible electronics, synthetic nerve cells, 500-mile range Tesla cars and batteries that allow us to stream Netflix on smartphones for weeks on end.