In the previous post in this series, I described some teaching skills that I subconsciously absorbed by reading works by Feynman. I also described some frustrations I had with what we were told to do in TA training.

What I learned from Preskill

Luckily for me, and hopefully for my students, the instructor for the first class I was a TA for (the upper division classical electrodynamics course) eventually gave me the freedom to really do things how I would want to, which, when I saw the results, led me to really ignore everything I was told. During the last week of the course, he said I could do whatever I wanted in the recitation sections since he was going to do review and talk about some advanced topics in lecture. It’s hard to know how all my experiences with good (and bad) teachers subconsciously influenced my teaching style, but the first time I remember consciously thinking about what kind of a teacher I wanted to be was the night before my first recitation section of the week, while I was planning my last lecture of the course. I distinctly remember reflecting on the following memories from my time at the IQI while trying to decide what to talk about and how to say it.

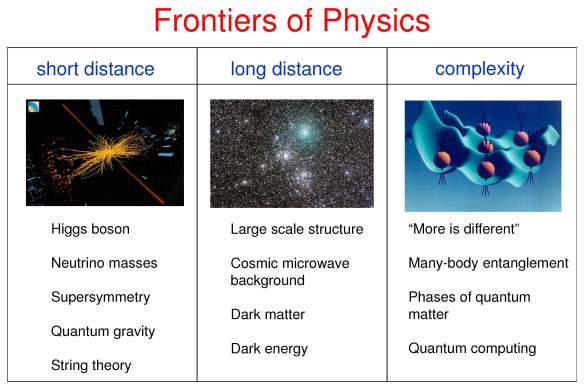

Once a week, John would run a two part group meeting. The first part consisted of everyone going around the room briefly summarizing what they had worked on for the past week, while the second consisted of a more traditional lecture about a specific topic of the speaker’s choice. At one point, one of the postdocs was in the middle of giving a series of lectures on a very technical subject. I was always struggling to follow them and stay interested and engaged in the discussion. I remember almost nothing from this particular series of lectures other than that the postdoc seemed to be trying to teach us every single detail about the subject rather than trying to give us a general feeling for what it was about. I’m sure it wasn’t so bad for the more advanced physicists in the room, and I bet I would get more out of them if I heard them again today.

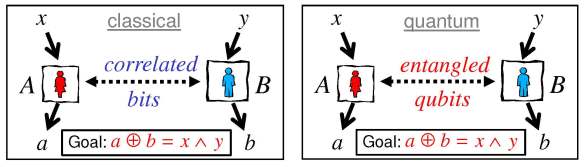

But then one marvelous week, John decided he was going to give the lecture instead. He started off by saying something along the lines of, “We have heard some very technical talks recently, which is good, and I have learned a lot from them. But sometimes it’s also good just to look at pictures.” He proceeded to give an extremely interesting, coherent, and inspiring lecture on black hole complementarity. I don’t think he ever wrote down a single equation, but I remember most of what he talked about and the pictures he drew to this day. I was honestly sad1 when the hour was up and was extremely excited to learn more. As soon as I got home that night, I read many papers on the subject of black holes and information, some of them John’s of course,2 for several hours and couldn’t have managed to get more than three hours of sleep.

This was not a unique experience with John’s masterful teaching technique. The summer I spent working at the IQI was one of the happiest times of my life since I got to spend so much time with so many scientists who I wasn’t even working with, including John. The project that I was supposed to be working on at the IQI was supervised by (then postdoc) Alexey Gorshkov and dealt with two-dimensional spin systems and efforts to simulate them experimentally. Although I greatly enjoyed working on that project, which actually went pretty well and led to my first paper, by far my favorite part of working at the IQI was getting to eat lunch with John and the rest of the group, in particular (then postdoc) Steve Flammia.

Most days as we would walk back to the IQI from the cafeteria, Steve would ask John some question, usually about quantum field theory or cosmology. (For example, “Why do some classical symmetries not survive quantization?”) By the time we got back to the lounge, John would have prepared the perfect lecture to answer Steve’s question, enlightening both to the most accomplished postdoc and the most naive undergrad. These lectures were amazing. I wish we had taped them so that I could watch them again. John did not shy away from equations when they were called for in these lectures, but they were still filled with pictures. (See Steve’s recollections of these lectures here and John’s here. The closest recorded lectures to John’s lunch lectures that I am aware of are some of Lenny Susskind’s more advanced courses from The Theoretical Minimum.3 The main difference between the two styles is that, due to the large discrepancy between the two audiences, John would compress something Susskind might explain into maybe a third to a quarter of the time Susskind would take. On occasion, John might use some slightly more sophisticated technology or go into a little more detail as well, but the essential style is very similar.)

I think John knew that I loved these lectures, but what he and Alexey might not know is that they were extremely detrimental to my productivity on the project that “I was supposed to be working on,” though I don’t think John would see it that way. After each of these lectures, I was forced to spend at least an hour reading textbooks or journal articles going into more detail on the topics John had just so masterfully discussed. Since I shared an office with Alexey, I often tried to hide what I was actually doing before getting back to work; I don’t think Alexey would have cared, but I wasn’t taking any chances. When I say “I was forced,” I literally mean that listening to John put me in a state of mind where I felt I had no choice but to read more. (Maybe John’s distinctive bedtime story voice makes him a kind of “snake charmer” of physicists by hypnotizing us into reading more physics.) Since John’s lectures always cut straight to the heart of any subject, this was the perfect way to learn something new or to clarify something found confusing before. Armed with a Preskill lecture and all the nice pictures fresh in my mind, it always seemed so easy to just start reading a technical account of something that I would certainly have found difficult without John’s introduction to it.

Figure 2.1: John Preskill, a “snake charmer” of physicists. Artwork by my uncle Eric Wayne.

Eventually, I was allowed to ask John the question on occasion, and sometimes Steve and I would discuss what we should ask John on the way back before we left for lunch. Of course, this great responsibility only caused me to read even more about things that “I was not supposed to be working on” so that we would have a better chance of having a real gem. (Occasionally, I was devastated to learn that Steve had already asked John some question that I had thought of like, “Why is CP violated?” I really wanted to hear that lecture, but Steve had already asked it, and there were no repeats.)

At the time, Steve claimed that his upcoming research appointment at the University of Washington required him to increase his knowledge of physics outside of quantum information and that asking John these questions was the perfect way to do that. This is partially accurate, though the truth is that Steve actually “knew” the answers, in a technical sense, to most of the questions he asked John; what was really important was to get an intuitive picture that could easily be lost when hearing or reading a very in-depth technical account of something. He wanted to “hear the story from a master” and in the process learn both some awesome physics and John’s “style,” i.e. to be able to give a deep, simple, and well organized argument on a wide range of subjects at a moments notice.4 In this sense, it almost didn’t matter what subject John actually lectured on, and I think this was the main reason for the somewhat vague “Why?” format in which most of these questions were phrased. Luckily for me, and my future students, I was able to get a good enough look at John’s “style” as well that I would be able to make an (imperfect) imitation when I became a TA about a year later.

In the next post, I’ll describe how, by trying to imitate John, I seemed to become a fairly popular TA.

- It might sound strange to be sad when a lecture is over, but that’s really the emotion I felt. Two other professors from my Caltech days, Niles Pierce and Hirosi Ooguri, come to mind whose lectures consistently made me sad when they were over—but in an excited way analogous to how one might feel when the episode of a favorite TV show ends while waiting for the next week. (These lectures on advanced mathematical methods in physics were the Ooguri lectures that made me really sad and are actually in English.) ↩

- I particularly remember reading about how black holes are mirrors and comments on a black hole’s final state. (Though see this paper, or this talk, for updated comments on the latter in light of the recent firewall controversy.) I also remember reading Susskind et. al.’s original paper on the subject that night. ↩

- The title for his courses is in reference to a comprehensive course of physics study that Lev Landau expected all of his students to pass. See here for an amusing, and somewhat terrifying, first hand account of what it was like to be one of the 43 students “to pass Landau’s minimum.” ↩

- S. Flammia, private correspondence. ↩