In the first post of this series, I described some frustrations I had with what we were told to do in TA training. In the previous post, I recalled some memories of interactions I had with John Preskill while I was working at the IQI.

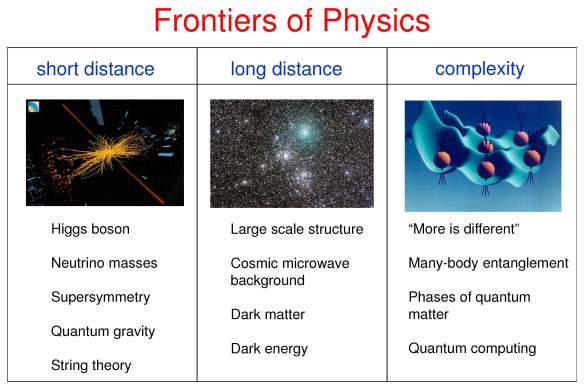

When it came time for me to give my last electrodynamics lecture, I remember thinking that I wanted to give a lecture that would inspire my students to go read more and which would serve as a good introduction to do just that—just as John’s lectures had done for me so many times. Now I am not nearly as quick as John,1 so I didn’t prepare my lecture in my head on the short walk from my office to the classroom where I taught, but I did prepare a lecture that I hoped would satisfy the above criteria. I thought that the way magnets actually work was left as a bit of a mystery in the standard course on electrodynamics. After toying around with a few magnet themes, I eventually prepared a lecture on the ferromagnetic-paramagnetic phase transition from a Landau-Ginzburg effective field theory point of view.2 The lecture had a strong theme about the importance and role of spontaneous symmetry breaking throughout physics, using magnets and magnons mainly as an example of the more general phenomenon. Since there was a lot of excitement about the discovery of the Higgs boson just a few months earlier, I also briefly hinted at the connection between Landau-Ginzburg and the Higgs. Keeping John’s excellent example in mind, my lecture consisted almost entirely of pictures with maybe an equation or two here and there.

This turned out to be one of the most rewarding experiences of my life. I taught identical recitation sections three times a week, and the section attendance dropped rapidly, probably to around 5–10 students per section, after the first few weeks of the quarter. Things were no different for my last lectures earlier in the week. But on the final day, presumably after news of what I was doing had time to spread and the students realized I was not just reviewing for the final, the classroom was packed. There were far more students than I had ever seen before, even on the first day of class. I remember saying something like, “Now your final is next week and I’m happy to answer any questions you may have on any of the material we have covered. Or if no one has any questions, I have prepared a lecture on the ferromagnetic-paramagnetic phase transition. So, does anyone have any questions?” The response was swift and decisive. One of the students sitting in the front row eagerly and immediately blurted out, “No, do that!”

So I proceeded to give my lecture, which seemed to go very well. The highlight of the lecture—at least for me because it is an example where a single physical idea explains a variety of physical phenomena occurring over a very large range of scales and because it demonstrated that at least some of the students had understood most of what I had already said—was when I had the class help me fill in and discuss Table 3.1. Many of the students were asking good questions throughout the lecture, several stayed after class to ask me more questions, and some came to my office hours after the break to ask even more questions—clearly after doing some reading on their own!

Table 3.1: Adapted from Table 6.1 of Magnetism in Condensed Matter. I added the last row and the last column myself before lecture. The first row was discussed heavily in lecture, the class helped me fill in the next two, and I briefly said some words about the last three. Tc is the critical temperature at which the phase transition occurs, M is the magnetization, P is the polarization, ρG is the Fourier component of charge density at reciprocal lattice vector G (as could be measured by Bragg diffraction), ψ and Δ are the condensate wavefunctions in a superfluid or superconductor respectively, φ is the Higgs field, BB = “Big Bang”, EW = “Electroweak”, and GUT = “Grand Unified Theory” (the only speculative entry on the list). The last two signify the phase transitions between the grand unified, electroweak, and quark epochs. Thanks to Alex Rasmussen and Dominic Else for heated arguments about the condensed matter rows that helped to clarify my understanding of them. To pre-empt Dominic yelling at me about Elitzur’s theorem, here is a very nice explanation by Francois Englert explaining, among other things, why gauge symmetries cannot technically be spontaneously broken. (This seems to be a question of semantics intimately related to how some people would say that gauge symmetries are not really symmetries—they’re redundancies. Regardless of what words you want to use, Englert’s paper makes it very clear what is physically happening.)

After that experience, I decided to completely ignore everything I was taught in TA training and to instead always try to do my best John Preskill imitation anytime I interacted with students. (Minus the voice, of course. There’s no replicating that, and even if I tried, hardly anyone would get the joke.) As I suggested earlier, a big frustration with what I was told to do was that—since UCSB has so many students with such a wide range of abilities—I should mostly aim my instruction for the middle of the bell curve, but could try to do some extra things to challenge the students on one tail and some remedial things to help the students on the other—but only if I felt like it. I’ve been told there’s no reason to “waste time” explaining how an idea fits into the bigger picture and is related to other physical concepts. Most students aren’t going to care and I could spend that time going over another explicit example showing the students exactly how to do something. I thought this was stupid advice and did it anyway, and in my experience, explaining the wider context was usually pretty helpful even to the students struggling the most.3

But when I started trying to imitate John by completely ignoring what I was supposed to do and instead just trying to explain exciting physics like he did, I seemed to become a fairly popular TA. I think most students appreciated being treated as naive equals who had the ability to learn awesome things—just as I was treated at the IQI. Instead of the null hypothesis being that your students are stupid and you need to coddle them otherwise they will be completely lost, make the null hypothesis that your students are actually pretty bright and are both interested in and able to learn exciting things, even if that means using a few concepts from other courses. But also be very willing to quickly and momentarily reject the null in a non-condescending manner. I concede the point that there are many arguments against my philosophy and that the anecdotal data to support my approach is potentially extremely biased,4 but I still think that it’s probably best to err on the side of allowing teachers to teach in the way that excites them the most since this will probably motivate the students to learn just by osmosis—in theory at least.

The last class I was a TA for (an advanced undergraduate elective on relativistic quantum mechanics) was probably the one that benefited the most from my attempts to imitate John, and me regurgitating things that I learned from him and a few others (see Figure 4.2 in the last post). The course used Dirac and Bjorken and Drell as textbooks, which are not the books that I would have chosen for the intended audience: advanced undergrads who might want to take QFT in the future.5 By that time, I was fully into ignoring what I was supposed to do and was just going to try to teach my students some interesting physics. So there was no way I was going to spend recitation sections going over, in quantitative detail, the Dirac Sea and other such outdated topics that Julian Schwinger would describe as “best regarded as a historical curiosity, and forgotten.”6 Instead, I decided right from the beginning, that I would give a series of lectures on an introduction to quantum field theory by giving my best guess as to the lectures John would have given if Steve or I had asked him questions such as “Why are spin and statistics related?,” or “Why are neutral conducting plates attracted to each other in vacuum?” Those lectures were often pretty crowded, one time so much so that I literally tripped over the outstretched legs of one of the students who was sitting on the ground in the front of the classroom as I was trying to work at the boards; all of the seats were taken and several people were already standing in the back. (In all honesty, that classroom was terrible and tiny.7 Nevertheless, at least for that one lecture, I would be surprised to learn that everyone in attendance was enrolled in the course.)

In the last post, I’ll describe some other teaching wisdom I learned from a few other good professors as well as concluding with some things I wish I had done better.

- Though I suspect a part of the reason that he is so quick to come up with these explanations is that he has thought deeply about them several times before when lecturing or writing papers on them. So maybe one day, after a few more decades of sustained effort, I will be able to approach his speed on certain topics that I’ve thought deeply about. ↩

- I mostly followed the discussion in Kardar: Fields for this part. When I went to write this post, I realized that there is a lecture of John’s on the same topic available here. ↩

- I bumped into one of my former students who occasionally struggled, but always made an honest effort to learn, about a year after I taught him last and he graduated and moved on to other things, and he felt it was necessary to thank me for doing these kinds of things. Although this is only one data point, the looks of relief on several students’ faces who I helped in office hours after explaining how what they were struggling with fit into the bigger picture leads me to believe that this is true more generally. ↩

- While almost all of the students who benefit from it are going to tell me, probably no one who would have preferred that I go over examples directly relevant to their assignments in great detail is going to tell me in front of those who are so excited about it. And I never got to see my teaching evaluations where the students may have been more comfortable criticizing my approach. ↩

- Dirac is an excellent book on non-relativistic quantum mechanics, and I remember finding it extremely useful when I read it as a supplement to Shankar and Cohen-Tannoudji while taking quantum mechanics as a sophomore at Caltech. However, the relativistic chapters are really old, though of course it’s fun to read about the Dirac equation from Dirac. Bjorken and Drell is also a classic, but it is also pretty old and, in my opinion, was way too technical for the intended audience. Quantum Field Theory for the Gifted Amateur by Lancaster and Blundell looks like a really good candidate for the class and the intended audience. In all fairness, that book hadn’t been published yet when the course was taught, but why we didn’t even use Zee or Srednicki is completely baffling to me—and both of them are even professors here, so it’s not like those books should have been unknown! (In my opinion, Zee would have been a great choice for that class, while Srednicki may be a slightly better choice for the graduate version.) ↩

- As quoted by Weinberg in Chapter 1, titled “Historical Introduction,” of The Quantum Theory of Fields. Reading that chapter made me feel like I would have been a TA for the history department rather than the physics department if I taught what I was expected to. It also made me cringe several times while typing up the solutions to the problem sets for the class, and, to atone for my sins, I felt like I had to do better in the recitation sections. ↩

- I also hated that room because it had whiteboards, instead of chalkboards, and so I couldn’t use another teaching skill, Lewin Lines, that I learned in high school from the great MIT physics professor Walter Lewin. (While I was in the editing stages of writing this post, I was very sad to learn of some recent controversy surrounding Lewin. Regardless of the awful things he has been accused of doing, if you’re going to be honest, you have to be able to separate that from his wonderful lectures which aspiring teachers should still try to learn from no matter what the truth turns out to be. I cannot rewrite history and pretend that watching all of his lectures didn’t provide me with a solid foundation to then read books such as Landau and Lifshitz or Jackson while still in high school. You also have to admit that Lewin Lines are really fun. After intense research (in collaboration with an emeritus head TA of the physics department) and much practice, I am, with low fidelity, able to make a bad approximation to the chalkboard Lewin Lines on a whiteboard—but they’re nowhere near as cool.) ↩