Last summer, I was blessed with the opportunity to learn about the basics of high temperature superconductors in the Yeh Group under the tutelage of visiting Professor Feng. We formed superconducting samples using a process known as Pulse Laser Deposition. We began testing the properties of the samples using X-Ray Diffraction, AC Susceptibility, and SQUIDs (superconducting quantum interference devices). I brought my new-found knowledge of these laboratory techniques and processes back into the classroom during this past school year. I was able to answer questions about the formation, research, and applications of superconductors that I had been unable to address prior to this valuable experience.

This summer I returned to the IQIM Summer Research Institute to continue my exploration of superconductors and gain even deeper research experience. This time around I have accompanied Caltech second year graduate student Kyle Chen in testing samples using the Scanning Tunneling Microscope (STM), some of which I helped form using Pulse Laser Deposition with Professor Feng last summer. I have always been curious about how we can have atomic resolution. This has been my big chance to have hands-on experience working with STM that makes it possible!

The Scanning Tunneling Microscope was invented by the late Heinrich Rohrer and Gerd Binnig at IBM Research in Zurich, Switzerland in 1981. STM is able to scan the surface contours of substances using a sharp conductive tip. The electron tunneling current through the tip of the microscope is exponentially dependent on the distance (few Angstroms) to the substance surface. The changing currents at different locations can then be compiled to produce three dimensional images of the topography of the surface on the nano-scale. Or conversely the distance can be measured while the current is held constant. STM has a much higher resolution of images and avoids the problems of diffraction and spherical aberration from lenses. This level of control and precision through STM has enabled scientists to use tools with nanometer precision, allowing scientists even to manipulate atoms and their bonds. STM has been instrumental in forming the field of nanotechnology and the modern study of DNA, semiconductors, graphene, topological insulators, and much more! Just five years after building their first STM, Rohrer and Binning’s work rightfully earned them the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Descending into the Sloan basement, Kyle and I work to prepare and scan several high temperature superconducting (HTSC) Calcium Doped YBCO samples in order better to understand the pairing mechanism that causes Cooper Pairs for superconductivity. In regular metals, the pairing mechanism via phonon lattice vibrations is fairly well understood by physicists. Meanwhile, the pairing mechanism for HTSC is still a mystery. We are also investigating how this pairing changes with doping, as well as how the magnetic field is channeled up vortices within HTSC.

One of our first tasks is to make probe tips for STM. Adding Calcium Chloride to de-ionized water, we are preparing a liquid conductive path to begin the chemical etching of the probe tip. Using a 10V battery, a wire bent into a ring is connected to the battery and placed in the Calcium Chloride solution. Then a thin platinum iridium wire, also connected to the voltage source, is placed at the center of the conductive ring. The circuit is complete and a current of about half an Ampere is used to erode uniformly the outer surface of the platinum iridium wire, forming a sharp tip. We examine the tip under a traditional microscope to scrutinize our work. Ideally, the tip is only one atom thick! If not, we are charged with re-etching until we reach a more suitable straight, uniform, sharp tip. As we work to prepare the platinum iridium tips, a stoic picture of Neils Bohr looks down at our work with the appropriate adjacent quotation, ” When it comes to atoms, language can be used only as in poetry. The poet, too, is not nearly so concerned with describing facts as with creating images. ” After making two or three nearly perfect tips, we clean and store them in the tip case and proceed to the next step of preparation.

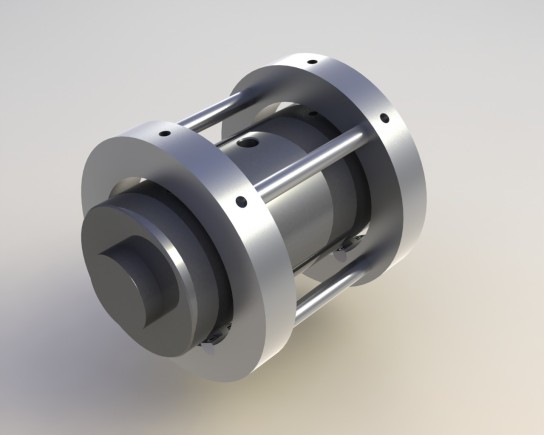

We are now ready to clean the sample to be tested. Bromine etching removes any oxidation or impurities that have formed on our sample, leaving a top bromine film layer. We remove the bromine-residue layer with ethanol and then plunge further into the (sub)basement to load the sample into the STM casing before oxidation begins again. The STM in the Yeh Lab was built by Professor Nai-Chang Yeh and her students eleven years ago. There are multiple layers of vacuum chambers and separate dewars, each with its own meticulous series of steps to prepare for STM testing. At the center is a long, central STM tube. Surrounding this is a large cylindrical dewar. On the perimeter is an exterior large vacuum chamber.

First we must load the newly etched YBCO sample and tip into the central STM tube. The inner tube currently lays across a work bench beneath desk lamps. We must transfer the tiny tip from the tip case to just above the sample. While loading the tip with an equally minuscule flathead screwdriver, it became quite clear to me that I could never be a surgeon! The superconducting sample is secured in place with a small cover plate and screw. A series of electronic tests for resistance and capacitance must be conducted to confirm that there are no shorts in the numerous circuits. Next we must vacuum pump the inner cylindrical tube holding the sample, tip, and circuitry until the pressure is Bar. Then we “bake” the inner chamber, using a heater to expel any other gas, while the vacuum pump continues until we reach approximately

Bar. The heater is turned off and the vacuum continues to pump until we reach

Bar. This entire vacuum process takes approximately 15 hours…

During this span of time, I have the opportunity to observe the dark, cold STM room. The door, walls and ceiling are covered with black rubber and spongy padding to absorb vibration. The STM room is in the lowest level basement for the same reason. The vibration from human steps near the testing generates noise in the data, so every precaution is made to minimize noise. Giant cement blocks lay across the STM metal box to increase inertia and decrease noise. I ask Kyle what he usually does with this “down” time. We discuss the importance of reading equipment manuals to grasp a better understanding of the myriad of tools in the lab. He says he needs to continue reading the papers published by the Yeh Lab Group. In knowing what questions your research group has previously answered, one has a better understanding of the history and the direction of current work.

The next day, the vacuum-pumped inner chamber is loaded to the center of the STM dewar. We flush the surrounding chambers with nitrogen gas to extricate any moisture or impurities that may have entered since our last testing. Next we can set up the equipment for a liquid nitrogen transfer which lasts approximately 2 hours, depending on the transfer rate. As the liquid nitrogen is added to the system, we meticulously monitor the temperature of the STM system. It must reach 80 Kelvin before we again test the electronics. Eventually it is time to add the liquid helium. Since liquid helium is quite expensive, additional precautions are taken to ensure maximum efficiency for helium use. It is beautiful to watch the moisture in the air deposit in frost along the tubing connecting the nitrogen and helium tanks to the STM dewar. The stillness of the quiet basement as we wait for the transfer is calming. Again, we carefully monitor the temperature drop as it eventually reaches 4.2 Kelvin. For this research, STM must be cooled to this temperature because we must drop below the critical temperature of the sample in order to observe superconductivity. The lower the temperature, the more of the superconducting component manifests itself. Hence the spectrum will have higher resolution. Liquid nitrogen is first added because it can carry over 90% of the heat away due to its higher mass. Nitrogen is also significantly cheaper than liquid helium. The liquid helium is added later, because it is even cooler than liquid nitrogen.

After adding additional layers of rubber padding on top of the closed STM, we can move over to the computer that controls the STM tip. It takes approximately one hour for the tip to be slowly lowered within range for a tunneling current. Kyle examines the data from the approach to the surface. If all seems normal, we can begin the actual scan of the sample!

An important part of the lab work is trouble shooting. I have listed the ideal order of steps, but as with life, things do not always proceed as expected. I have grown in awe of the perseverance and ingenuity required for daily troubleshooting. The need to be meticulous in order to avoid error is astonishing. I love that some common household items can be a valuable tool in the lab. For example, copper scrubbers used in the kitchen serve as a simple conducting path around the inner STM chamber. Floss can be used to tie down the most delicate thin wires. I certainly have grown in my immense respect for the patience and brilliance required in real research.

I find irony in the quiet simplicity of recording and analyzing data, the stillness of carefully transferring liquid helium juxtaposed to the immense complexity and importance of this groundbreaking research. I appreciate the moments of simple quiet in the STM room, the fast paced group meetings where everyone chimes in on their progress, or the boisterous collaborative brainstorming to troubleshoot a new problem. The summer weeks in the Sloan basement have been a welcome retreat from the exciting, transformative, and exhausting year in the classroom. I am grateful for the opportunity to learn more about superconductors, quantum tunneling, vacuum pumps, sonicators, lab safety, and more. While I will not be bromine etching, chemically forming STM tips, or doing liquid helium transfers come September, I have a new-found love for the process of research that I will radiate to my students.