Einstein and I have both been spooked by entanglement. Einstein’s experience was more profound: in a 1947 letter to Born, he famously dubbed it spukhafte Fernwirkung (or spooky action at a distance). Mine, more pedestrian. It came when I first learned the cost of entangling logical qubits on today’s hardware.

Logical entanglement is not easy

I recently listened to a talk where the speaker declared that “logical entanglement is easy,” and I have to disagree. You could argue that it looks easy when compared to logical small-angle gates, in much the same way I would look small standing next to Shaquille O’Neal. But that doesn’t mean 6’5” and 240 pounds is small.

To see why it’s not easy, it helps to look at how logical entangling gates are actually implemented. A logical qubit is not a single physical object. It’s an error-resistant qubit built out of several noisy, error-prone physical qubits. A quantum error-correcting (QEC) code with parameters uses physical qubits to encode logical qubits in a way that can detect up to physical errors and correct up to of them.

This redundancy is what makes fault-tolerant quantum computing possible. It’s also what makes logical operations expensive.

On platforms like neutral-atom arrays and trapped ions, the standard approach is a transversal CNOT: you apply two-qubit gates pairwise across the code blocks (qubit in block A interacts with qubit in block B). That requires physical two-qubit gates to entangle the logical qubits of one code block with the logical qubits of another.

To make this less abstract, here’s a QuEra animation showing a transversal CNOT implemented in a neutral-atom array. This animation is showing real experimental data, not a schematic idealization.

The idea is simple. The problem is that can be large, and physical two-qubit gates are among the noisiest operations available on today’s hardware.

Superconducting platforms take a different route. They tend to rely on lattice surgery; you entangle logical qubits by repeatedly measuring joint stabilizers along a boundary. That replaces two-qubit gates for stabilizer measurements over multiple rounds (typically scaling with the code distance). Unfortunately, physical measurements are the other noisiest primitive we have.

Then there are the modern high-rate qLDPC codes, which pack many logical qubits into a single code block. These are excellent quantum memories. But when it comes to computation, they face challenges. Logical entangling gates can require significant circuit depth, and often entire auxiliary code blocks are needed to mediate the interaction.

This isn’t a purely theoretical complaint. In recent state-of-the-art experiments by Google and by the Harvard–QuEra–MIT collaboration, logical entangling gates consumed nearly half of the total error budget.

So no, logical entanglement is not easy. But, how easy can we make it?

Phantom codes: Logical entanglement without physical operations

To answer how easy logical entanglement can really be, it helps to start with a slightly counterintuitive observation: logical entanglement can sometimes be generated purely by permuting physical qubits.

Let me show you how this works in the simplest possible setting, and then I’ll explain what’s really going on.

Consider a stabilizer code, which encodes 4 physical qubits into 2 logical ones that can detect 1 error, but can’t correct any. Below are its logical operators; the arrow indicates what happens when we physically swap qubits 1 and 3 (bars denote logical operators).

You can check that the logical operators transform exactly as shown, which is the action of a logical CNOT gate. For readers less familiar with stabilizer codes, click the arrow below for an explanation of what’s going on. Those familiar can carry on.

Click!

At the logical level, we identify gates by how they transform logical Pauli operators. This is the same idea used in ordinary quantum circuits: a gate is defined not just by what it does to states, but by how it reshuffles observables.

A CNOT gate has a very characteristic action. If qubit 1 is the control and qubit 2 is the target, then: an on the control spreads to the target, a on the target spreads back to the control, and the other Pauli operators remain unchanged.

That’s exactly what we see above.

To see why this generates entanglement, it helps to switch from operators to states. A canonical example of how to generate entanglement in quantum circuits is the following. First, you put one qubit into a superposition using a Hadamard. Starting from , this gives

At this point there is still no entanglement — just superposition.

The entanglement appears when you apply a CNOT. The CNOT correlates the two branches of the superposition, producing

which is a maximally-entangled Bell state. The Hadamard creates superposition; the CNOT turns that superposition into correlation.

The operator transformations above are simply the algebraic version of this story. Seeing

tells us that information on one logical qubit is now inseparable from the other.

In other words, in this code,

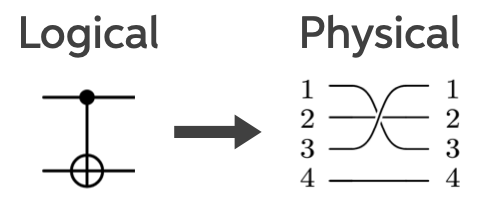

The figure below shows how this logical circuit maps onto a physical circuit. Each horizontal line represents a qubit. On the left is a logical CNOT gate: the filled dot marks the control qubit, and the ⊕ symbol marks the target qubit whose state is flipped if the control is in the state . On the right is the corresponding physical implementation, where the logical gate is realized by acting on multiple physical qubits.

At this point, all we’ve done is trade one physical operation for another. The real magic comes next. Physical permutations do not actually need to be implemented in hardware. Because they commute cleanly through arbitrary circuits, they can be pulled to the very end of a computation and absorbed into a relabelling of the final measurement outcomes. No operator spread. No increase in circuit depth.

This is not true for generic physical gates. It is a unique property of permutations.

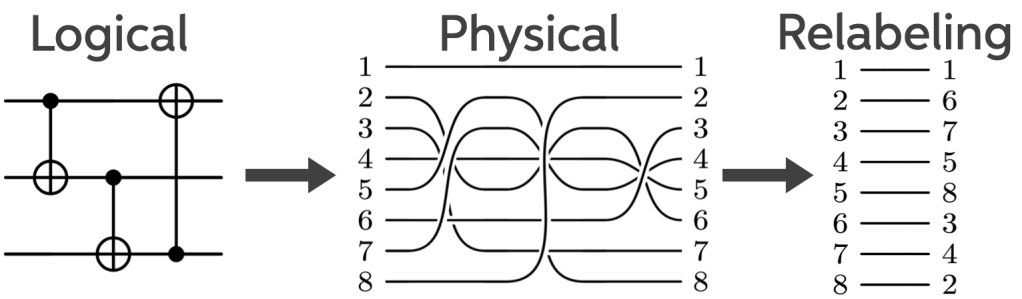

To see how this works, consider a slightly larger example using an code. Here the logical operators are a bit more complicated:

Below is a three-logical-qubit circuit implemented using this code like the circuit drawn above, but now with an extra step. Suppose the circuit contains three logical CNOTs, each implemented via a physical permutation.

Instead of executing any of these permutations, we simply keep track of them classically and relabel the outputs at the end. From the hardware’s point of view, nothing happened.

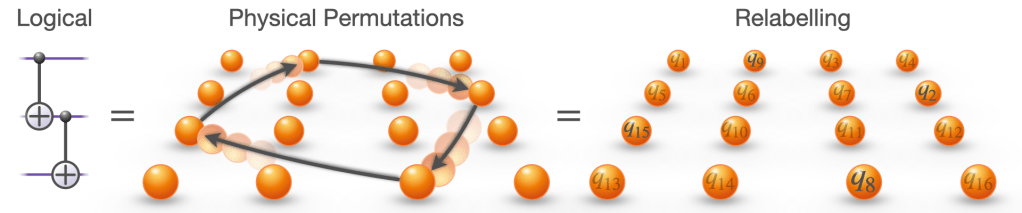

If you prefer a more physical picture, imagine this implemented with atoms in an array. The atoms never move. No gates fire. The entanglement is there anyway.

This is the key point. Because no physical gates are applied, the logical entangling operation has zero overhead. And for the same reason, it has perfect fidelity. We’ve reached the minimum possible cost of a logical entangling gate. You can’t beat free.

To be clear, not all codes are amenable to logical entanglement through relabeling. This is a very special feature that exists in some codes.

Motivated by this observation, my collaborators and I defined a new class of QEC codes. I’ll state the definition first, and then unpack what it really means.

Phantom codes are stabilizer codes in which logical entangling gates between every ordered pair of logical qubits can be implemented solely via physical qubit permutations.

The phrase “every ordered pair” is a strong requirement. For three logical qubits, it means the code must support logical CNOTs between qubits , , , , , and . More generally, a code with logical qubits must support all possible directed CNOTs. This isn’t pedantry. Without access to every directed pair, you can’t freely build arbitrary entangling circuits — you’re stuck with a restricted gate set.

The phrase “solely via physical qubit permutations” is just as demanding. If all but one of those CNOTs could be implemented via permutations, but the last one required even a single physical gate — say, a one-qubit Clifford — the code would not be phantom. That condition is what buys you zero overhead and perfect fidelity. Permutations can be compiled away entirely; any additional physical operation cannot.

Together, these two requirements carve out a very special class of codes. All in-block logical entangling gates are free. Logical entangling gates between phantom code blocks are still available — they’re simply implemented transversally.

After settling on this definition, we went back through the literature to see whether any existing codes already satisfied it. We found two. The Carbon code and hypercube codes. The former enabled repeated rounds of quantum error-correction in trapped-ion experiments, while the latter underpinned recent neutral-atom experiments achieving logical-over-physical performance gains in quantum circuit sampling.

Both are genuine phantom codes. Both are also limited. With distance , they can detect errors but not correct them. With only logical qubits, there’s a limited class of CNOT circuits you can implement. Which begs the questions: Do other phantom codes exist? Can these codes have advantages that persist for scalable applications under realistic noise conditions? What structural constraints do they obey (parameters, other gates, etc.)?

Before getting to that, a brief note for the even more expert reader on four things phantom codes are not. Phantom codes are not a form of logical Pauli-frame tracking: the phantom property survives in the presence of non-Clifford gates. They are not strictly confined to a single code block: because they are CSS codes, multiple blocks can be stitched together using physical CNOTs in linear depth. They are not automorphism gates, which rely on single-qubit Cliffords and therefore do not achieve zero overhead or perfect fidelity. And they are not codes like SHYPS, Gross, or Tesseract codes, which allow only products of CNOTs via permutations rather than individually addressable ones. All of those codes are interesting. They’re just not phantom codes.

In a recent preprint, we set out to answer the three questions above. This post isn’t about walking through all of those results in detail, so here’s the short version. First, we find many more phantom codes — hundreds of thousands of additional examples, along with infinite families that allow both and to scale. We study their structural properties and identify which other logical gates they support beyond their characteristic phantom ones.

Second, we show that phantom codes can be practically useful for the right kinds of tasks — essentially, those that are heavy on entangling gates. In end-to-end noisy simulations, we find that phantom codes can outperform the surface code, achieving one–to–two orders of magnitude reductions in logical infidelity for resource state preparation (GHZ-state preparation) and many-body simulation, at comparable qubit overhead and with a modest preselection acceptance rate of about 24%.

If you’re interested in the details, you can read more in our preprint.

Larger space of codes to explore

This is probably a good moment to zoom out and ask the referee question: why does this matter?

I was recently updating my CV and realized I’ve now written my 40th referee report for APS. After a while, refereeing trains a reflex. No matter how clever the construction or how clean the proof, you keep coming back to the same question: what does this actually change?

So why do phantom codes matter? At least to me, there are two reasons: one about how we think about QEC code design, and one about what these codes can already do in practice.

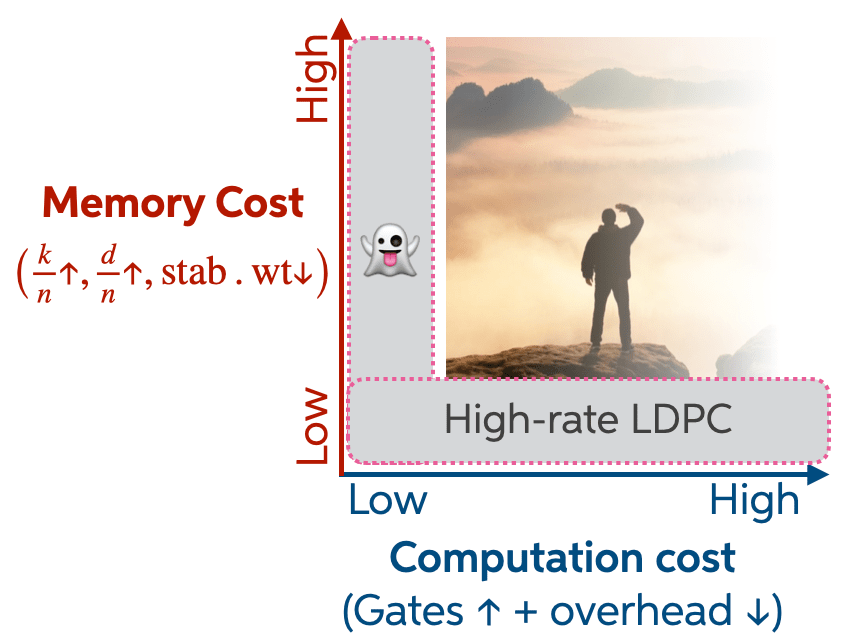

The first reason is the one I’m most excited about. It has less to do with any particular code and more to do with how the field implicitly organizes the space of QEC codes. Most of that space is structured around familiar structural properties: encoding rate, distance, stabilizer weight, LDPC-ness. These form the axes that make a code a good memory. And they matter, a lot.

But computation lives on a different axis. Logical gates cost something, and that cost is sometimes treated as downstream—something to be optimized after a code is chosen, rather than something to design for directly. As a result, the cost of logical operations is usually inherited, not engineered.

One way to make this tension explicit is to think of code design as a multi-dimensional space with at least two axes. One axis is memory cost: how efficiently a code stores information. High rate, high distance, low-weight stabilizers, efficient decoding — all the usual virtues. The other axis is computational cost: how expensive it is to actually do things with the encoded qubits. Low computational cost means many logical gates can be implemented with little overhead. Low computational cost makes computation easy.

Why focus on extreme points in this space? Because extremes are informative. They tell you what is possible, what is impossible, and which tradeoffs are structural rather than accidental.

Phantom codes sit precisely at one such extreme: they minimize the cost of in-block logical entanglement. That zero-logical-cost extreme comes with tradeoffs. The phantom codes we find tend to have high stabilizer weights, and for families with scalable , the number of physical qubits grows exponentially. These are real costs, and they matter.

Still, the important lesson is that even at this extreme point, codes can outperform LDPC-based architectures on well-chosen tasks. That observation motivates an approach to QEC code design in which the logical gates of interest are placed at the centre of the design process, rather than treated as an afterthought. This is my first takeaway from this work.

Second is that phantom codes are naturally well suited to circuits that are heavy on logical entangling gates. Some interesting applications fall into this category, including fermionic simulation and correlated-phase preparation. Combined with recent algorithmic advances that reduce the overhead of digital fermionic simulation, these code-level ideas could potentially improve near-term experimental feasibility.

Back to being spooked

The space of QEC codes is massive. Perhaps two axes are not enough. Stabilizer weight might deserve its own. Perhaps different applications demand different projections of this space. I don’t yet know the best way to organize it.

The size of this space is a little spooky — and that’s part of what makes it exciting to explore, and to see what these corners of code space can teach us about fault-tolerant quantum computation.